Words by Amanda Sturgeon

Artwork by Lea Colombo

Buildings can be icons of joy: They can connect us to the essence of a place, bring a culture to life, and serve as vessels that connect people and nature.

So often, though, they don’t live up to that potential. Instead, they consume vast amounts of natural resources, have devastating impacts on biodiversity, and focus more on maximizing square footage than performing a societal or environmental duty of care. Our built environment needs an intervention, and biomimicry—redesigning our world based on nature’s genius—can provide the pathway back to buildings that work with planetary boundaries.

At its worst, our built environment cuts us off from the natural world, destroying that world through irresponsible building practices in the process. At its best, it connects us to the living world, is constructed using materials that do minimal harm to the planet, and draws inspiration from the vibrant lives and forms taking shape all around us. To achieve that latter vision, we can integrate practices of biomimicry into our architecture.

I’ve seen the power of this approach firsthand. As a fresh architecture graduate in 1998, Janine Benyus’s book Biomimicry was a pivotal influence on my quest to unite people and nature through the built world. It was a subject that was often met with resistance during my studies, but the concept of biomimicry opened an entirely new palette of design opportunities for me.

When I joined the design team at Seattle-based Architects Mithun to work on the beautiful IslandWood center in Bainbridge Island, Washington in 1999, learning from and emulating the beauty of the Pacific Northwest giant forests was front of mind.

By the 2000s, the influence of Biomimicry was beginning to filter through to the realm of architecture. Architects had become curious about nature’s 3.8 billion years of brilliance and adaptation and wanted to learn from biologists about how nature works. A few influential projects emerged, such as the Eden Project by Grimshaw Architects in Cornwall, U.K. The project, a series of interconnected biomes, required a lightweight dome structure, so the team studied lightweight structures in nature, such as bubbles, and discovered that the geodesic arrangement of pentagons and hexagons created the lightest structural forms. These were mimicked to create an incredibly lightweight structure that also resulted in substantial cost savings due to less steel being needed in the structure. The project showed that learning from nature’s functions could unleash new innovative approaches to the challenges that emerge in the design process and in addition to being cost effective.

As contemporary architects started integrating biomimicry in the mid 2000s, the sector began paying attention to the onset of climate science data outlining how much buildings contribute to the climate crisis. The focus then pivoted to carbon reduction and a silo of disconnected “Band-Aid” climate solutions arose.

When they are not designed in response to the local climate and unique conditions of their place, buildings consume a lot of energy. We see glass towers in Singapore and Alaska that look so similar we can barely tell them apart, built from the same materials, that cost massive amounts of carbon to transport, not to mention the energy needed to cool or heat the buildings once they’re constructed. But over the last five years, the realization has finally begun to dawn that nature and climate are interconnected—and that business and property portfolios take on a large amount of risk when nature’s systems start to collapse. A new phase that involves looking to nature for solutions to reduce risk is upon us.

Biomimetic architecture can take many different paths. Buildings can mimic the function of a species or ecosystem in the building’s form, in the way that the building operates, by using nature-inspired building materials, or by continuing to provide the ecosystem services of the place where it’s constructed. Biophilic design, an adjacent approach, seeks to reconnect people and nature in the built environment––and one pathway to achieve that can be through mimicking the types of experiences and spaces that are present in nature, such as the sensory variations experienced while walking through a forest.

The field is as rich with solutions and ideas as nature is, and it’s high time those solutions spread.

“Many of the solutions inspired by nature are not new, they’ve just been forgotten or ignored.”

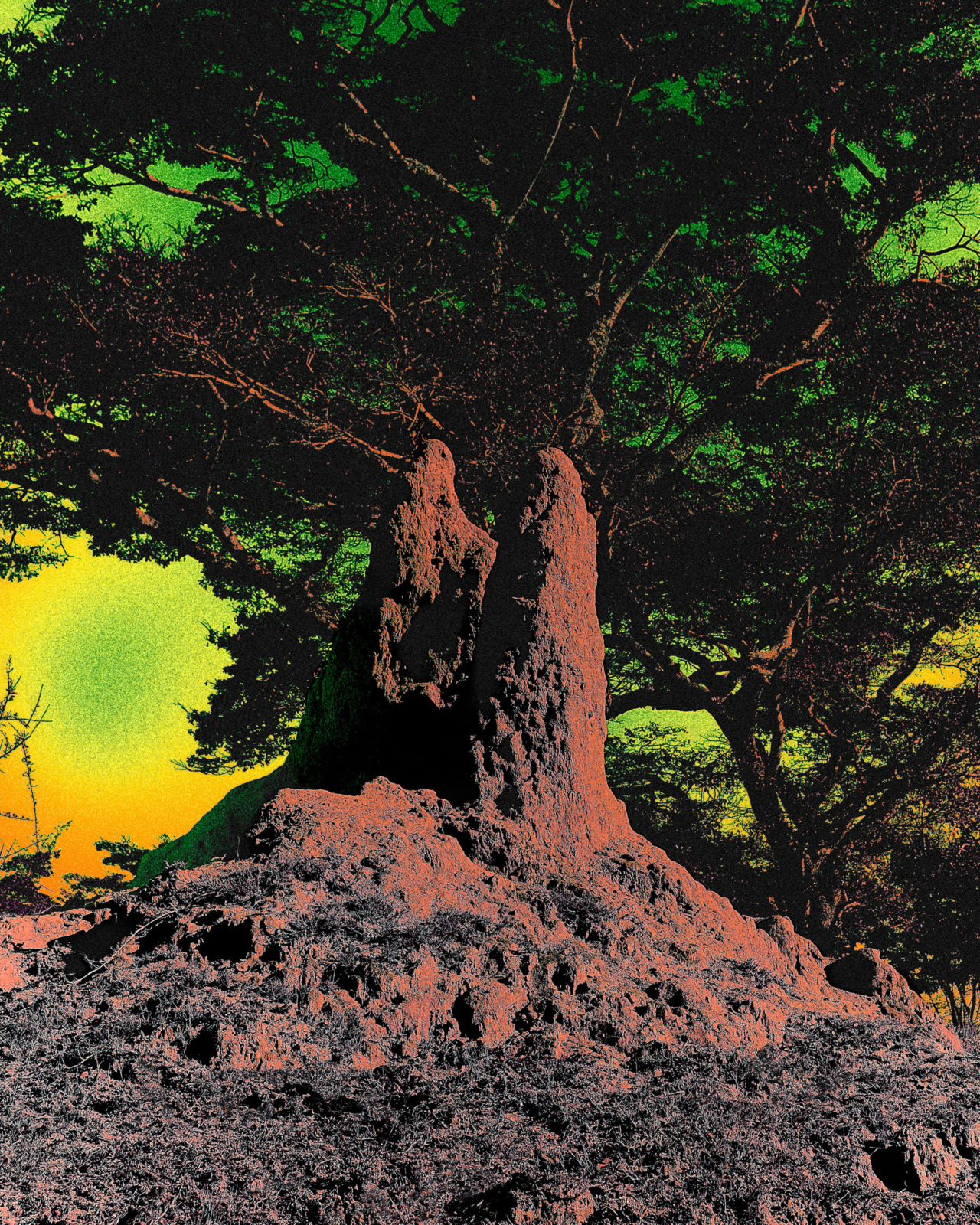

A range of contemporary projects, such as the Eastgate Center in Zimbabwe, by architect Mick Pearce, have referenced the function of the termite mound in their design, allowing natural ventilation to once again replace energy-consuming cooling solutions. The termite mound has a natural air conditioning system that funnels hot air out of a sort of chimney at the top, consequently drawing in cooler air from the bottom to replace it. It is a time-tested approach in buildings, as traditional Middle Eastern architecture demonstrates, and is based on the simple physics of hot air rising above cold. Many of the solutions inspired by nature are not new, they’ve just been forgotten or ignored.

The Bullitt Center in Seattle, designed by Miller Hull Architects in 2013, was influenced by the giant Douglas fir trees of the region––not in shape and look, but in function. As an advisor to the project and its first tenant, I experienced firsthand how the plentiful rain of Seattle was captured by the building, cleaned, and then either used in the building or re-entered into the aquifer in support of keystone species such as salmon and orca whales. Amid a sea of buildings that simply flushed clean rainwater into the sewage system, The Bullitt Center’s unique construction sparked change in regulations and policies, and the building provided more value in ecosystem services to the region than it cost to build.

There are also buildings and bridges by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. At the Milwaukee Art Museum, for example, he designed a moveable shading structure that references the appearance and movement of a bird’s wing, rather than the aerodynamic function. Foster & Partners’ Gherkin tower in London draws inspiration from marine organisms such as the Venus’ flower basket sponge. Its shape reduces wind deflection on the outside while the internal atria facilitate air movement through the inside, mimicking the ways the sponge’s forms function to move water currents around and through itself.

A new materials economy is also mimicking nature’s brilliance. The Ray of Hope Accelerator at the Biomimicry Institute, where I now serve as CEO, has supported a range of new innovations from companies such as Mycocycle, which is inspired by fungi to transform waste materials into valuable low-carbon biobased materials. Biohm uses mycelium to create insulation products that can be grown as a replacement for the current products that depend on minerals and require large amounts of energy to produce. The bio-inspired materials market was valued at $47.4 billion in 2024 and is projected to increase to $89.9 billion by 2035.

If we look to nature, we will find systemic solutions that create conditions conducive to all life. In doing so, we can address not just energy consumption, but also the biodiversity impacts of supply chains, the toxicity of our contemporary building practices, and the overall “take-make-waste” economy that is having dire consequences on nature and people.

Biomimicry’s influence could pivot the entire building industry to address multiple impacts systemically. Nature does not work in silos––it works with the principles of collaboration, interconnectedness, and mutual benefit for the entire system. The architecture sector needs to break free from singular issue foci. Learning from nature’s genius can form the path to that freedom.

Production Casa Colombo Assistant Roberto Colombo

These images by Lea Colombo juxtapose the architecture of Zimbabwe’s Eastgate Centre—a biomimetic building modeled after a termite mound’s ventilation system—with real termite mounds.

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 12: Pollinate with the headline, “Architecting Tomorrow With Biomimicry.”

The Promise of Biomimicry: When Buildings Breathe Like Termite Mounds