Words by Cristina Mittermeier

Photographs by Cristina Mittermeier / SeaLegacy

What if I told you the key to solving the climate crisis isn’t just technology or policy, but a whale frolicking freely in the ocean, or a seagrass meadow swaying gently in the current?

For too long, the living fabric of our planet has been invisible to our economic systems, its worth reduced to what can be harvested, extracted, or consumed. But what if nature’s greatest services—storing carbon, cleaning air and water, regulating the climate—had a dollar value we could no longer ignore? One of the world’s top economists is helping us imagine what that would look like.

Last year, my partner Paul Nicklen and I were on an expedition aboard our boat, the SeaLegacy 1. We were exploring Raja Ampat, Indonesia, home to some of the most biologically rich coral reef ecosystems on Earth.

Paul and I founded our nonprofit, SeaLegacy, to leverage the power of photography and storytelling to inspire meaningful action for ocean conservation. On this trip, we wanted to try something new: Instead of photographing the usual charismatic megafauna, we turned our lenses to the tiny creatures barely visible to the naked eye. We thought night dives would be perfect for this.

One night, I had my head buried in a reef, focusing my camera on a shrimp, when I suddenly had the feeling of being watched. I turned around and came face-to-face with a bigfin reef squid.

No larger than a small flashlight, he was curious and unafraid. He fluttered over my shoulder as I turned my lights toward him. When the lights hit him, he got very excited and gave me the show of a lifetime! Octopus, cuttlefish, and squid have specialized cells, called chromatophores and iridophores, that allow them to shift color and reflect light in dazzling displays.

For the better part of an hour, I played hide-and-seek with this little creature, transfixed by his beauty, curiosity, and astonishing ability to change colors. How sad it is to think that most people will only ever know this animal as deep-fried calamari on a plate and will only get to experience it swimming in mayonnaise. Squid’s value, in today’s world, only exists once it’s dead. And even then, that value is estimated at only a few dollars. The living squid I encountered that night—priceless in its beauty and wonder, as well as in the role that it plays in maintaining the delicate biochemistry of our planet—has a dollar value of zero.

This way of thinking reflects a deep flaw in how our global economy values nature. It tends to only see value in nature once it is dead and extracted, as in the case of fish, timber, and minerals. It does not see what living nature does for us every day. In ecology, we refer to these contributions as ecosystem services, and they’re typically categorized into three main types: provisioning (providing food or fuel), cultural (encompassing spiritual or recreational value), and regulating. Regulating services are perhaps the most critical for sustaining life on Earth. And yet, they’re the least recognized, the least valued, and the most urgently in need of our attention.

We’re living through a twin crisis of climate change and biodiversity loss. These aren’t separate problems; rather, they are inextricably intertwined. As climate change rapidly disrupts habitats, species that have taken thousands of years to adapt struggle to keep up and face challenges to their survival. And as species vanish, we lose the very biodiversity that keeps Earth liveable by purifying our air and water, cycling nutrients, and absorbing carbon.

The good news is we can reframe this way of thinking. Climate change and biodiversity loss may be fueling one another, but the inverse is also true: A solution to one can feed solutions to the other. If we protect and restore biodiversity, we restore the planet’s ability to regulate itself, and we begin to address the climate crisis at its root.

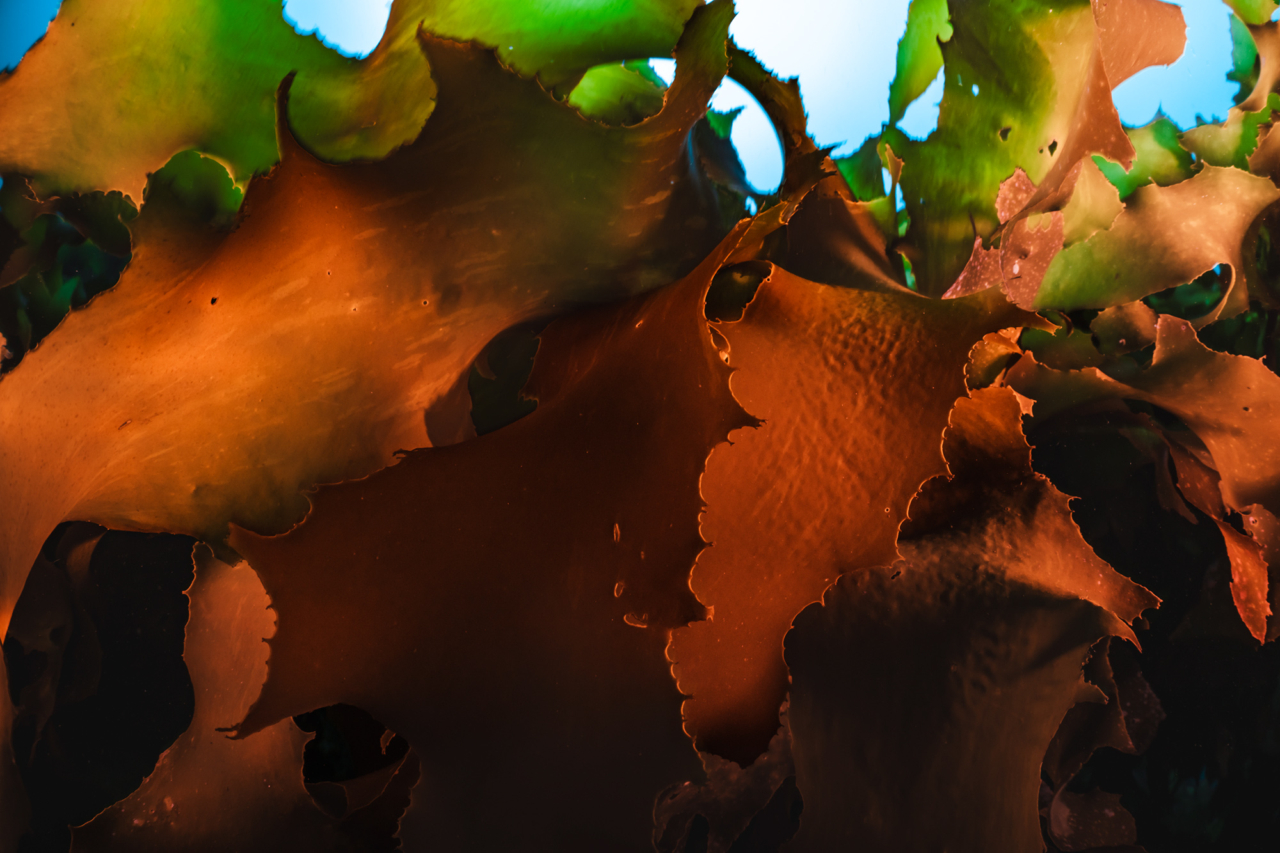

The first place we should look is the ocean. The ocean is the largest ecosystem on Earth, and it plays a dominant role in regulating the planet’s climate. It produces more than half the oxygen we breathe and absorbs vast amounts of carbon. Marine algae, from microscopic phytoplankton to towering kelp forests, act as carbon pumps. They draw CO₂ from the atmosphere and pass it up the food web. When marine animals defecate or die, they deposit carbon in the deep sea, where it stays locked away for centuries.

Unfortunately, these services are not valued in modern economies. While carbon markets exist, they’ve historically ignored the ocean’s role in climate regulation and failed to account for the true value of living nature. Our economic systems, still rooted in Industrial-era thinking, continue to treat nature as infinite and external.

That failure has come at a cost. In 2024, climate disasters cost the world over $320 billion. That doesn’t account for the carbon those damaged ecosystems could have continued to store or the cascading impacts of their loss. It is ironic that we are willing to pay more after disaster strikes than we are willing to pay to prevent it.

To truly succeed in addressing these twin crises of climate change and biodiversity loss, a paradigm shift is necessary. But education and love for nature aren’t always enough to drive systemic change. We need to speak the language the whole world understands: the language of money.

There’s no one better to bridge the gap between economy and nature than my dear friend Ralph Chami, visionary economist and CEO of Blue Green Future. In 2017, he recognized that if we can calculate the market value of fish or timber, then surely we can do the same for living nature.

“Education and love for nature aren’t always enough to drive systemic change. We need to speak the language the whole world understands: the language of money.”

Before that, Ralph worked for the International Monetary Fund for 23 years, focusing on economic policy and capacity development across the Middle East and North Africa. But an experience on the ocean sparked a seismic shift in his approach to economics. While onboard a tiny whale research vessel, he overheard scientists discussing carbon storage in whales, and something clicked: If a whale stores carbon, and carbon has a market price, then that whale’s service must have financial value. Seeing a blue whale changed everything for Ralph. The experience filled him with such profound awe that it altered the course of his life.

Whales eat enormous amounts of krill and other minuscule organisms in the ocean, store that carbon in their bodies, and fertilize the photic zone with their nutrient-rich waste. This boosts the growth of phytoplankton, which draws more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and feeds the next generation of krill, completing the cycle.

Based on current carbon market values, Ralph estimated that a single whale contributes approximately $2 million in ecosystem services over its lifetime. In other words, without that whale, we would need to spend $2 million elsewhere to offset the same amount of carbon.

Ralph’s calculations didn’t stop at whales. His organization now collaborates with governments and NGOs to assess the market value of ecosystem services, ranging from individual species, like elephants, to entire ecosystems.

“Creating a market for regenerative nature is a matter of translating the value of ecosystem services into a language the markets can understand,” said Ralph. “It is then about providing data about the condition of the natural asset that the market can trust.”

To understand the impact of Ralph’s work, it is helpful to know how carbon markets operate and why many have failed. In theory, these markets allow polluters to offset their emissions by funding projects that sequester carbon. But in practice, those projects have often lacked transparency, scientific rigor, and community involvement, which has understandably eroded trust.

Ralph’s approach aims to change that. His model prioritizes community engagement and transparency, focusing on nature-based solutions that use advanced technology and science to quantify the carbon sequestration of living ecosystems. Satellite monitoring and dynamic modeling are used to verify the health of the ecosystem and accurately measure the carbon it stores.

One of the most exciting examples of this approach is unfolding in the Bahamas, where the world’s largest seagrass ecosystem was discovered just a few years ago. Seagrass, which absorbs carbon up to 35 times faster than a rainforest, is a vital yet often overlooked ally in mitigating climate change.

Shortly after the discovery, SeaLegacy played a key role in helping to connect the dots and unleash its full potential. We traveled to the Bahamas to capture the seagrass ecosystem’s beauty and share stories of its importance to both marine life and the climate. It gives me immense pride to know our work has finally paid off.

Earlier this year, the Bahamian government announced its partnership with Laconic, a climate technology company, to launch Sovereign Carbon Securities for their seagrass ecosystem. These are insured, tradable financial assets that allow countries or corporations to invest in seagrass restoration as a verified carbon offset. The aim is not to sell the ocean itself, but to sell the services a living ocean provides.

The proceeds are allocated toward protecting those ecosystems in perpetuity, while ensuring that local communities benefit directly from their stewardship. In fact, 93% of proceeds from carbon sales are reinvested directly into local communities, tracked on a public data ledger to ensure transparency and trust.

In a world driven by capital and extraction, I believe this offers a hopeful blueprint that invites markets to recognize the value of intact, living nature. This planet is the only one we have, and most of it is blue. If we hope to survive, we must learn to see it in its entirety. And if the only way we, as a species, can begin to comprehend its worth is through the language of dollar signs, then I am glad that conversation has finally begun.

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 12: Pollinate with the headline, “The Economic Case for Marine Conservation.”

The Ocean Is the World’s Most Undervalued Economy