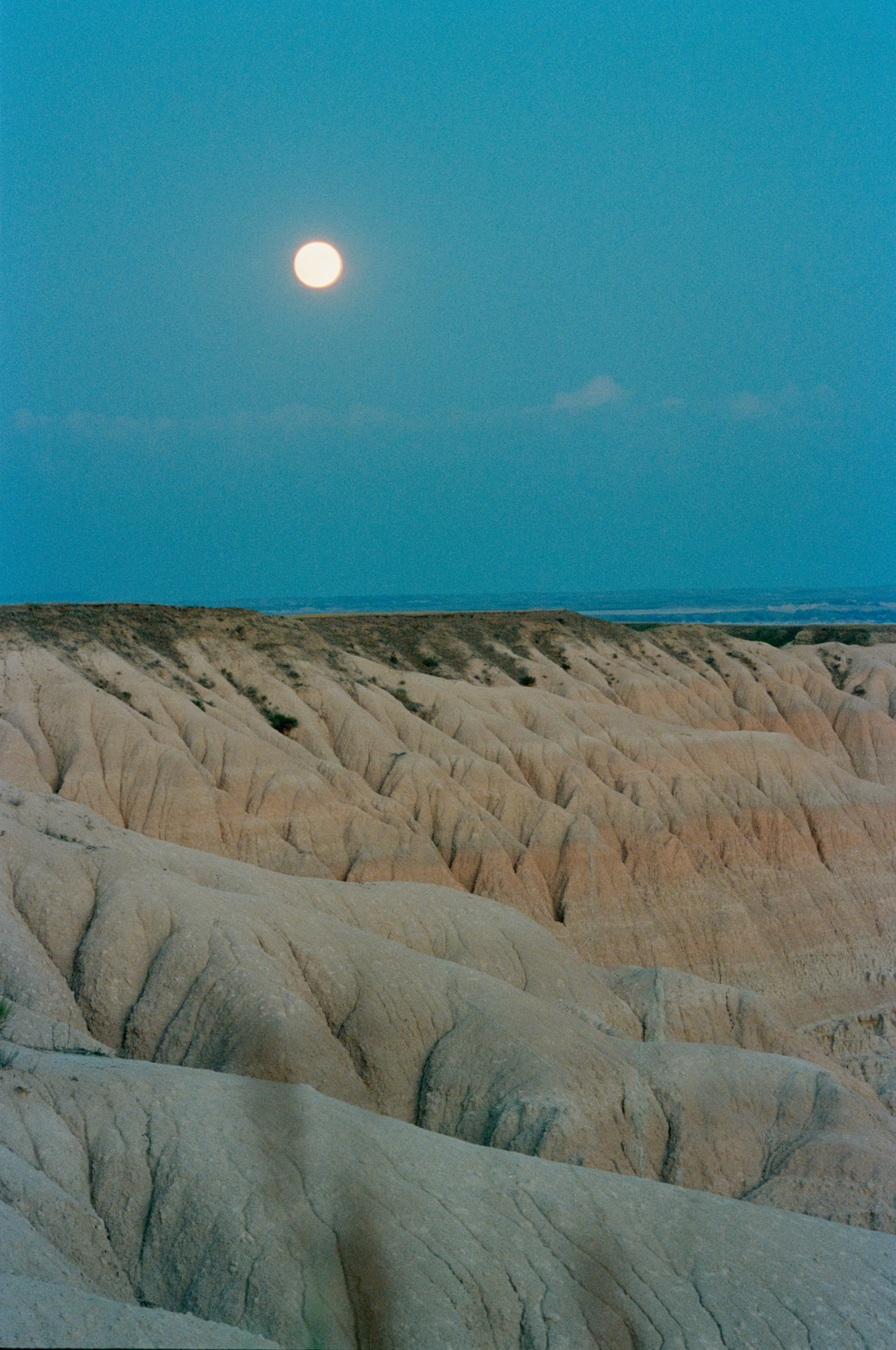

In this series, photographer Rahim Fortune captures the vast landscape of Badlands National Park alongside the enduring presence of the Oglala Lakota Tribe, tracing how their history and resilience continue to shape the story of the land.

Words by Jade Begay

Photographs by Rahim Fortune

Within the first few months of the second Trump administration, as the outcome of a widely criticized Republican proposal to sell off up to 3.3 million acres of federal public lands remained undecided, a pressing question began to echo: Could Tribes or Indigenous communities purchase these public lands if they were truly put up for sale?

The question, while grounded in hope, revealed a deeper anxiety about the future of land stewardship in the United States. Since early 2025, when the Trump administration began dismantling proper management of public and federal lands by laying off or forcing out thousands of National Park Service employees, proposing $1.2 billion in cuts (a staggering 35–40% of the agency’s funding), and proposing the logging of 59% of U.S. Forest Service lands, the public discourse has reflected mounting unease. What happens when the federal government walks away from the very lands it is entrusted to protect?

The idea that Indigenous communities might take over that role is, on the surface, a promising one, borne of the belief that Tribes exercising sovereignty over more land would benefit people and planet alike. But to realize that vision in any meaningful way, Tribes need to be properly resourced—in terms of capital, infrastructure, training, and legal authority.

Seeking some clarity on what it might take for that dream to become a reality, I called Thomas Linzey, a friend and Senior Legal Counsel at the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights (CDER), to cut through the fog of wishful thinking.

Linzey didn’t mince words. “If the public lands were really being sold, the only way Tribes could protect those lands would be to buy [them]. That means raising a huge amount of money,” he told me. “Sadly, that’s not likely. Philanthropy just doesn’t give that kind of capital to Indigenous communities. It’s also unlikely that nonprofits could buy up large amounts of land either. Developers with lots of money would likely win those bids.”

Plus, he went on, “if we had the capital to do these types of purchases, we would’ve done that already, not with public lands per se, but in other large chunks of land.”

It’s a sobering assessment, but for me, it wasn’t surprising. I’ve spent years working alongside Indigenous-led groups focused on conservation, restoration, biodiversity, and regenerative land practices. The barrier of capital—of having reliable, sizable, long-term funding—comes up constantly. And buying land, monumental as that is, is only the beginning.

What we don’t discuss as much is what happens after a “land back” win. How do communities maintain stewardship, build infrastructure, and regenerate ecosystems while simultaneously supporting their people?

One place I often turn to for inspiration—and reality—is the Native Conservancy, an Indigenous-led nonprofit based in Alaska that protects both land and ocean ecosystems through Native-led trusts and regenerative mariculture. After years of activism and advocacy in the wake of the devastating Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, Dune Lankard founded the Native Conservancy in 2003. He and his team have helped protect over one million acres along the Gulf of Alaska coastline in the years since.

When I asked him about misconceptions surrounding Indigenous conservation, he didn’t hold back.

“People think Indigenous-led conservation is mostly symbolic—prayers, land acknowledgments, or protecting ‘sacred’ wilderness. But the truth is, it’s about survival. It’s about sovereignty, stewardship, and feeding our people—today, not someday,” Lankard told me. “At Native Conservancy, our daily work includes harvesting kelp, delivering wild foods to elders, building community-owned seed nurseries, training youth in dive safety and ocean farming, and outfitting hybrid vessels for clean marine operations. It’s about equipping Native communities with the tools, training, and rights to protect the places we come from.”

Far too often, there’s a deeply unproductive romanticization of “land back” or Indigenous stewardship. People imagine a kind of decolonized Eden—free from modern machinery or material needs. The assumption is that because this work is Indigenous-led, it requires less: less capital, less infrastructure, fewer tools.

Others lean into the equally problematic idea that Native communities are just inherently resilient and capable of doing more with less. While it’s true that Indigenous Peoples have shown remarkable adaptability over generations of dispossession and neglect, it is unjust to use resilience as an excuse to deny them what’s truly needed: investment, infrastructure, trust-based funding, and legal authority.

If we’re serious about equity—and especially if we’re serious about repair—we need to resource Indigenous stewardship with the same urgency and scale as we fund top-down climate tech or conservation NGOs.

In the context of the U.S., the question of whether Tribes could assume management of federal lands that are currently at risk of mismanagement or sale has a tragically straightforward answer. Under the Trump administration’s current policy trajectory, the answer is no.

Co-management or co-stewardship agreements, which commit Tribes and the Federal government to collaboration and shared approaches to land management—and which can align with treaties, uphold sovereignty, and promote environmental resilience and strengthen climate adaptation—already exist. But instead of expanding these kinds of agreements, the federal government is stripping away basic supports that Indigenous communities rely on—not to mention stripping funds away from current co-management projects such as Badlands National Park and its unique relationship with the Oglala Sioux Tribe.

Funding for Medicaid, the largest source of health coverage for Native Americans, is being slashed. Clean energy infrastructure projects are being halted. Tribal economic development programs, Native agriculture support, and even Tribal media funding are under attack.

“Those lands should go back to Tribal management and ownership. But you have to believe that this administration is not going to do that,” Linzey told me. “This Administration didn’t even consult the Tribes on the draft rule that was being made on the sale of the public lands, even though most of the public lands are in traditional Tribal territory…This administration is not going to do anything to help the Tribes. They’re stripping the federal government for parts, and they’re going to sell to the highest bidder.”

We’re living in an anti-democratic moment, in which short-term political gains are being financed by long-term environmental destruction. The colonial myth of Manifest Destiny still lingers, not only in ideology, but in active policy: extract, sell, profit, repeat. What makes this moment so disorienting—and painful—is that even as Indigenous leaders continue to offer solutions, their access to land, power, and capital remains minimal.

Consider what happened to the Native Conservancy earlier this year. In 2024, the organization and a Tribal partner in Southeast Alaska were awarded a significant grant from the Environmental Protection Agency under the Biden administration, tied to the historic Inflation Reduction Act. This grant would have been transformative.

But in the spring of 2025, it was terminated.

“We’re expected to lead climate solutions, but without land, without investment, and without power in the system. That’s the real barrier,” Lankard reflected. “We’ve built Native-owned kelp cooperatives, created a Guardian Ocean Monitoring program to track ocean health, launched dive and kelp farming training for rural and Native youth, and developed mariculture planning frameworks grounded in culture. But we’re doing this with short-term grants and constant uphill battles for access and recognition. We don’t lack vision or capacity—we lack long-term, trust-based investment and land and ocean access that reflects our rights and relationships.”

As I listened, I couldn’t help but think of how often I’ve heard one particular statistic quoted at climate conferences: “Indigenous Peoples and local communities manage 54% of the world’s remaining intact forests.”

It’s repeated like a mantra. But rarely does it come with the acknowledgment of what it actually takes—financially, emotionally, spiritually, logistically—to manage those forests. More often than not, this statistic is used to inspire, but not to fund. It fuels the narrative without supporting the people holding the line.

That’s beginning to shift. The nonprofit One Earth, for example, recently released their “Minding the Gaps: Climate Finance Report” and launched the One Earth Solutions Finance Tracker. Through One Earth’s tools and research, we now have clear data telling us that nature-based solutions, specifically conservation efforts that center Indigenous land tenure, are some of the most effective ways to combat climate change, but they are drastically underfunded.

When I spoke with Justin Winters, Executive Director of One Earth, she shared these alarming findings: “Our Solutions Finance Tracker project highlights the overconcentration of capital in certain ‘charismatic’ areas and a critical underfunding of essential and highly effective nature conservation efforts. Our findings show that a significant portion of the $17 trillion expected to be deployed by 2030 could be misallocated without a clear, science-based strategy that prioritizes not only the specific solutions we need to scale, but also where we most urgently need to focus our collective efforts.”

Tools like this are extremely necessary so that we can direct meaningful capital to Indigenous-led solutions, moving beyond lip service toward structural change.

But funding alone won’t solve the problem. As we look toward more permanent protections that last beyond the boom and bust cycle of federal policy, we must consider legal frameworks that recognize nature’s own rights.

According to the Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights, “the ‘rights of nature’ is the recognition and protection of legal rights of nature, including rights of ecosystems and species. Rights of nature laws, policies, and court decisions recognize nature as a living entity with legal rights. Further, they institute mechanisms for people and governments to implement, enforce, and defend these rights on behalf of, and in the name of, nature.”

In 2023, CDER launched the Land that Owns Itself program, a bold legal initiative that envisions ecosystems not as property, but as self-owning, self-governing entities. The program is meant to help the law take the “next big systemic leap, such that nature is not only protected with legal rights, but is moved out from under human control and ownership, to become self-owned and self-governed,” according to the CDER program overview.

This framework resonates deeply with Indigenous worldviews, while providing enforceable legal structures that are sorely needed. After all, one of the greatest frustrations of environmental advocacy is watching hard-fought gains rolled back every election cycle. The Rights of Nature legal strategy could provide the long-term protection that our communities, and the planet, deserve.

So we return to the question: Who gets to care for the land when the state walks away? If the answer is Indigenous communities, we must go beyond slogans and into action—action that redistributes land, wealth, power, and legal agency. We must stop asking Indigenous Peoples to protect biodiversity without giving them the land or resources to do it.

And we must remember: Nature is not ours to own. It is a living system we belong to, and our task—at this late and urgent hour—is to learn how to live in right relationship again.

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 12: Pollinate with the headline, “Beyond Landback.”

Returning the Commons to Indigenous Hands