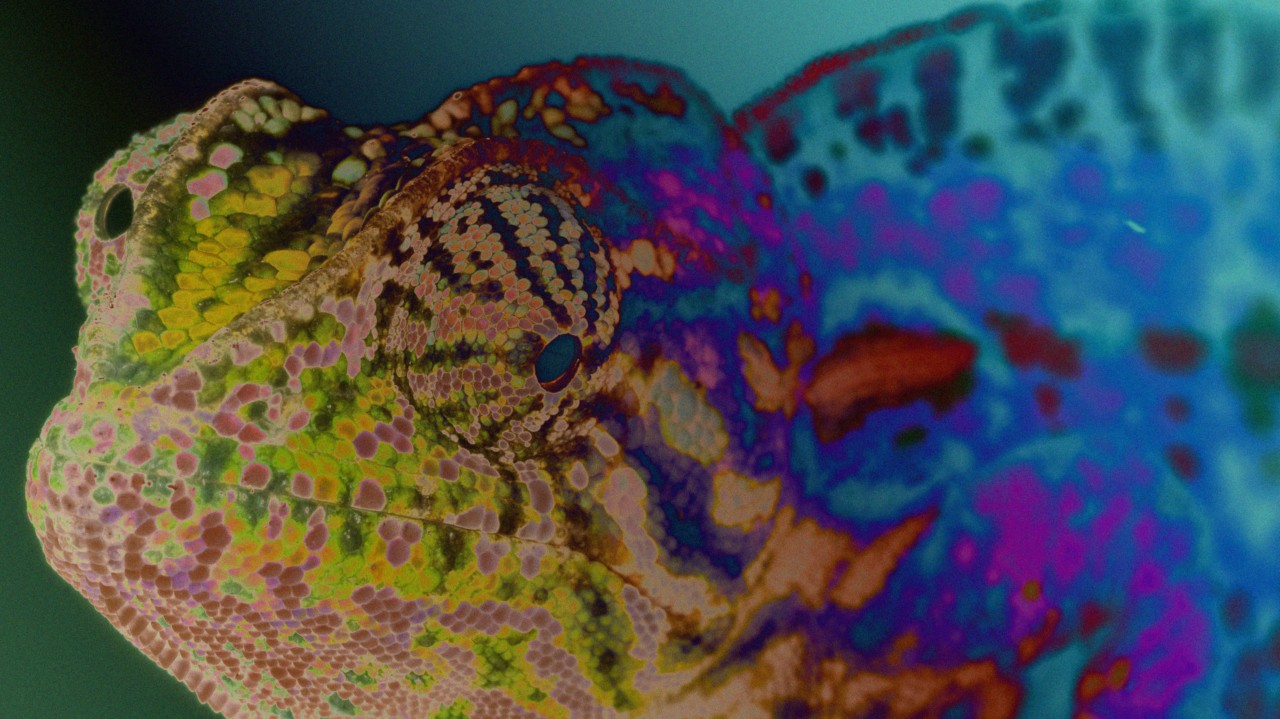

Photograph by Alexis Rosenfeld / Getty Images

WORDS BY KATE LOCKHART

Deep under the towering Brazil nut trees, fruiting acai palms, and flocks of scarlet macaws, a young Benki Piyãko watched his grandfather disappear into the thick forest shadows of the Amazon. “Here is where you will learn,” he recalled his grandfather telling him. “The forest speaks, but you must be silent to hear it.”

Baptized as a Wenki life warrior at age 2 and trained as the Ashaninka’s pajé, the keeper of traditions and healing wisdom, Piyãko leads his community in wildlife conservation, agroforestry, and building a thriving, sovereign municipality in Marechal Thaumaturgo.

The Ashaninka mission has always been to protect the forest, rivers, animals, and knowledge passed down by their ancestors. “For us, the forest is like our mother—it provides everything we need to live,” Piyãko said. But sitting on the stoop of Yorenka Tasorentsi Institute, which the Ashaninka people founded in 2018 to spread their teachings, Piyãko grieved the devastation to non-human life caused by government and industrial pursuits in the region.

“They are being killed by humans because the forest can’t speak like us. Animals can’t talk like we do, and the water can’t. It’s a suicide that humanity is committing,” Piyãko said. “We’re going to die together.”

Amidst unprecedented global change, Piyãko returns with the lesson his grandfather once taught him: to listen to each other, to nature, and to the silence we hold within. For many, the din of the outside world can drown out that dialogue—but not Piyãko and his people. Like their ancestors, the Ashaninka turn to a traditional medicine that helps them hear what the Earth is saying: the plant-based, psychedelic tea called ayahuasca.

“When we drink the ayahuasca, we are entering into a relationship,” Piyãko said. “A conversation with the spirit of the plant.” This conversation guides their decisions about everything from where to plant trees to how to stop the bulldozers razing their forests.

“If you listen deeply, you will know what to do, Piyãko added. “The Earth is always speaking.”

What Ashaninka and other nature-based people see as connecting with the spirits of more-than-human life, psychedelic researchers like Dr. David Yaden of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine describe as mind perception, or “an attribution for the capacity for consciousness.”

Sometimes I see people taking the plants but forgetting the forest. They want the wisdom, but not responsibility. That is not our way. The forest and the medicine are one. You cannot separate them.”

As Piyãko teaches, engaging in interspecies conversations guides environmental action. Once people recognize beings as conscious, they’re more likely to protect them. Could this phenomenon bolster climate action more broadly? Amidst a widening human-nature disconnect, mind perception could be exactly what the environmental movement needs.

Yaden became interested in the phenomenon after hearing people tell stories about how taking psychedelics altered their worldviews, many sharing a newfound belief in the consciousness of non-human beings.

The science is still in its infancy, and initial studies have yielded mixed results. A 2022 study co-authored by Yaden found that after taking a classic psychedelic, survey respondents were more likely to agree that non-human primates, four-legged animals, insects, plants, fungi, natural objects, and the universe are capable of having conscious experiences. This effect persisted even eight years after psychedelic use. However, a more robust, prospective longitudinal study published last year by Yaden and colleagues found much weaker results. When it comes to psychedelics changing people’s beliefs in the long term, “the data just don’t seem to be supporting that view,” Yaden said. “It would be kind of surprising, right? A six-hour experience changing your whole belief about how the world works.”

One possible reason for the inconsistent results is that the effects of psychedelic use depend on set and setting. The user’s mindset, environment, and mindful processing influence how they make sense of the experience. Yaden said it can be tempting to attribute any changes to the psychoactive substance; that “you put this molecule into the nervous system and voilà, you get more mind perception and pro-environmental behaviors.” But it’s the context that matters. “If you take these substances in a context in which ecosystems and the environment are highly emphasized, then there could be effects of this sort,” he said, “and maybe they’ll be lasting.”

The Ashaninka agree with researchers. Taking psychedelics as a singular experience or in an artificial setting won’t lead to a more connected relationship with the natural world or to greater environmental stewardship. “Sometimes I see people taking the plants but forgetting the forest,” Piyãko said. “They want the wisdom, but not responsibility. That is not our way. The forest and the medicine are one. You cannot separate them.”

For the Ashaninka, who have developed a relationship with plant medicines over millennia, the context is a loving, reciprocal connection with the natural world. It’s why the Yorenka Tasorentsi Institute has planted more than 2 million trees and saved several fish and wildlife populations from extinction.

“We are doing our part. Planting, teaching, protecting, healing. But we need others to walk with us. Not just to take from the forest, but to stand for it. To remember it is alive.”

Other organizations around the globe are increasingly embracing the spirit of nature and reciprocity. TreeSisters in the United Kingdom focuses on ecological restoration and community empowerment by partnering with communities in Brazil and Uganda, including Yorenka Tasorentsi. Executive Director Georgina Gorman explained that the charity’s program pillars—receptivity, reciprocity, and respect—shape the organization’s approach to ethical reforestation. The success of TreeSisters’ tree-planting projects skyrocketed after adopting this framework. “Nature has its own consciousness,” Gorman said. “We recognize the deep wisdom in seeing nature as alive, interconnected, and worthy of respect,”

Society at large isn’t quite there. Today’s people are profoundly separated from each other and the natural world. Piyãko sees this clearly: “I have walked in many countries, and what I see is that people are thirsty for meaning, for connection,” he said. “But they are afraid to change. They have forgotten that we are all part of one life. Not separate—one.”

This goes a long way in explaining the positive outcomes of psychedelic treatments on people with mental health issues. Yaden recalled a study of psilocybin treatment on people with anxiety that asked participants whether they felt “connected to everything” on the day of their treatment. Those who reported a higher sense of connectedness also reported significantly lower levels of anxiety and depression weeks and months later. Connectedness also predicts more positive outcomes for PTSD.

What stands as a revelation for Western scientists defines the Ashaninka culture. “In our culture, the plant medicines are not separated from community,” Piyãko explained. “Healing is not individual, it is collective. And that is something the modern world has forgotten.”

Piyãko sees universal connectedness—nurtured by the wisdom of psychedelic plant medicines—as the salve to today’s environmental unraveling.

“Our grandparents told us this time would come. That there would be much confusion. That people would lose their path. But they also said that those who remember how to listen to the Earth would help others return,” said Piyãko. “We are doing our part. Planting, teaching, protecting, healing. But we need others to walk with us. Not just to take from the forest, but to stand for it. To remember it is alive.”

Can Psychedelics Help Heal Our Relationship With the Natural World?