Words by Dina Fine Maron

Photographs by Jacques Brun

Finding a dead wandering albatross is an incredibly rare event. The gigantic bird, known for its unparalleled 11-foot wingspan and its epic flights, typically dies at sea. Yet shortly after Christmas 2023, at a remote bird research station 1,000 miles from the tip of Antarctica, Ash Bennison saw several.

Worried and in search of answers, he and his colleagues quickly suited up in white Tyvek suits, face masks, gloves, goggles, and green rubber boots to swab the animals’ noses and butts.

“That was an alarm bell moment,” said Bennison, a marine ecologist and the science manager of the research station on Bird Island, a tiny spit of land located off the northwest point of South Georgia Island in the South Atlantic Ocean. The area is an essential wildlife refuge for many of the world’s penguins, seals, and various threatened marine birds, and British Antarctic Survey scientists, including Bennison’s colleagues, had been tracking the area’s wandering albatrosses and other seabird colonies for decades, so the deaths felt like a personal blow to them. But at such an isolated spot, any deadly pathogen also raised potential concerns for human health, too.

They sent the swabs to England—first via a Falkland Islands-bound ship and then onward by plane. About two months later, after more than 50 albatrosses had died, the results came back. They were what Bennison had both suspected and feared: highly pathogenic avian flu.

In some ways, the main surprise was that it had taken so long for this virus to tear through the species at all. The latest version of H5N1 has proven particularly lethal as it has buffeted the world’s birds—and mammals—since it was found in European birds in 2020. Its reach has been shocking, spilling over from wild waterfowl and domestic poultry into animals as varied as mountain lions, seals, bears, deer, mink, foxes, cows and, in extremely rare cases, humans. In captivity, more than 80 million birds at U.S. poultry farms alone have died from the virus or been culled in an attempt to stave off further spread.

This avian flu outbreak is just one example of animal spillover that’s recently left scientists with troubling questions about the health of our planet and our role in emerging disease threats. “Human interactions and actions can have a role in this and many other potential zoonotic diseases,” said Colin Basler, the deputy director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s One Health Office.

Although humans have been on the planet for only a tiny fraction of Earth’s history—less than 1% of its existence—our alterations to our habitat, including deforestation, climate change, and mass animal farming, have fueled seismic shifts in the ecosystem and brought us into closer contact with species that have fewer places to go—setting the stage for the ever-growing list of emerging diseases that arise from animal spillover. The numbers are staggering: Almost all human infectious diseases—as many as 75%—originally circulated in animals before jumping to humans.

“We are interacting with animals in different ways, and human populations are growing and moving into new spaces,” said Basler. That heightens the risks of disease spread even though connecting the dots between human actions and specific spillover events can be challenging.

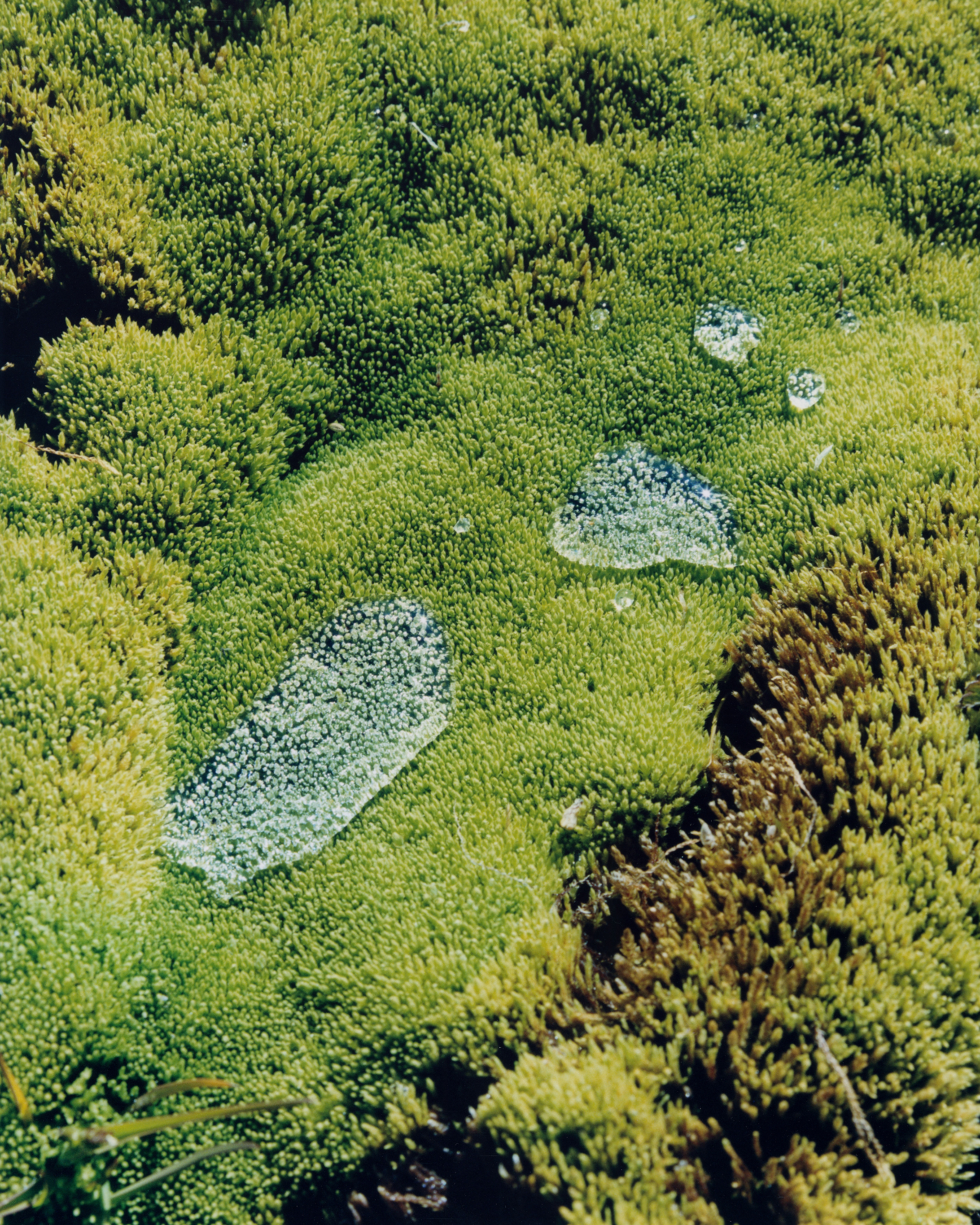

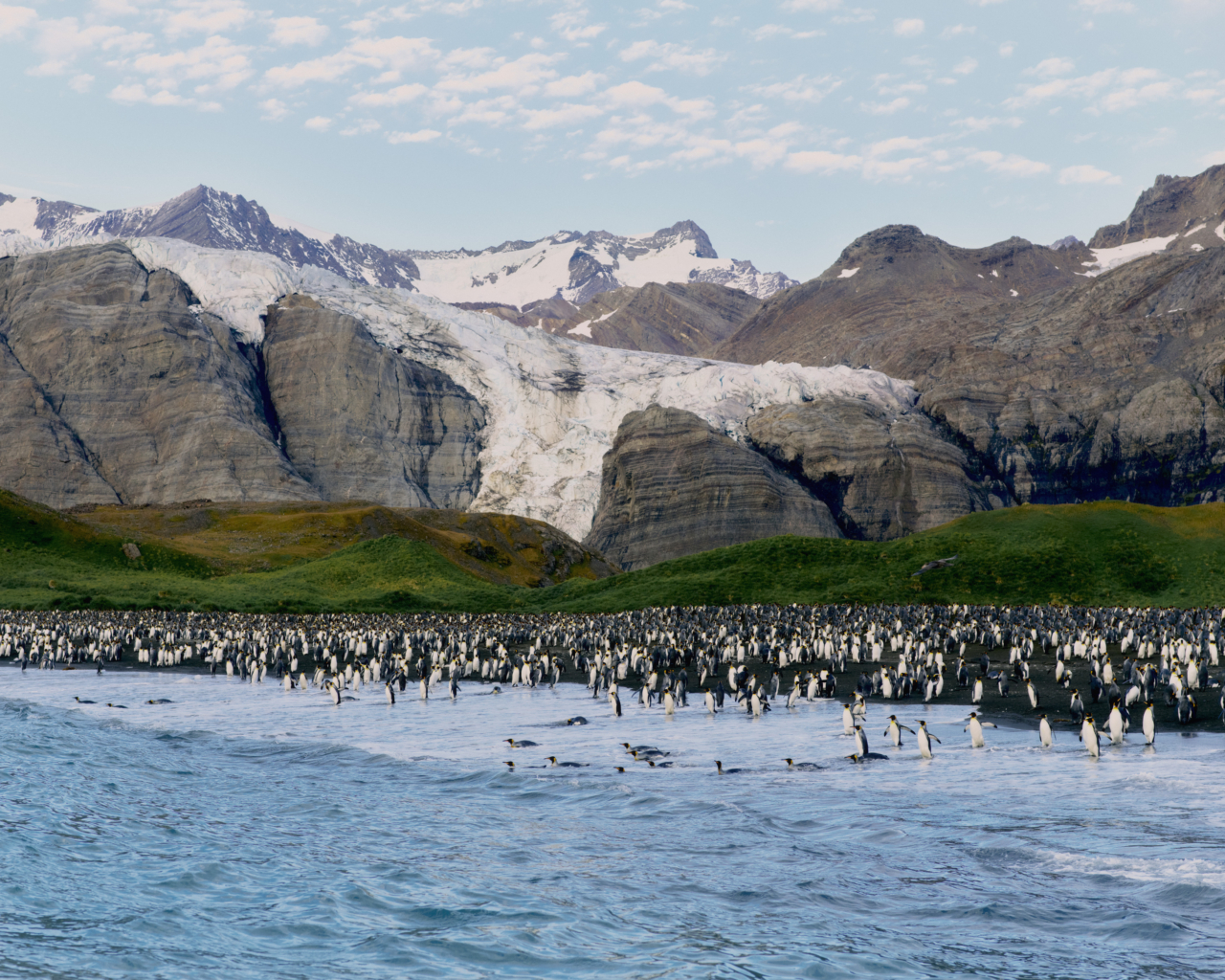

Now, those ripple effects are being seen in wildlife locales as far flung and pristine as South Georgia, an island off the coast of Antarctica and the southernmost tip of South America. The area is so incredibly remote and inhospitable to humans that only a small number of researchers stay there at any given time, alongside the thousands of birds and seals that breed in the largely undisturbed habitat.

In just the past decade, said Neil Vora, a former disease detective at the CDC and now the pandemic prevention fellow at the nonprofit Conservation International, several other emerging diseases with zoonotic links have defied public health expectations, underscoring the need to act quickly. With Ebola, the wild card was that it could be transmitted sexually. With Zika virus, it was that a mosquito-borne disease could cause birth defects. With COVID, it has been that the virus can spread even before people show symptoms.

This H5N1 avian flu outbreak has also astonished experts with its tenacity and the diversity of animals it can infect and kill, Vora said. If we wait to see when and if pathogens can readily be passed between humans, he noted, it will be too late.

Already, shortly after Bennison’s bad albatross news, there was new cause for concern. In early 2024, the virus touched down in mainland Antarctica—the first time highly pathogenic avian flu had ever been found on the continent. The virus, found in dead seabirds, might put Antarctica’s beloved and densely packed penguins at risk, Bennison said, but another major concern is that if a massive number of penguins perish, it could have larger knock-on effects for the food system. “In truth, we’re not certain what the long-term impacts of that would be, but unfortunately we may yet find out,” he said.

Despite humanity’s long familiarity with avian influenzas, they remain enigmatic. Transmission seems to happen when birds interact with disease-laden poop or scavengers eat sick birds, yet exactly how this specific pathogen is shuttling between species is largely unknown. The virus can be spread in respiratory secretions and can even survive on contaminated farm equipment or in water sources, according to the CDC. Though avian flu isn’t yet adept at being passed from one human to another, there’s evidence that sick humans can infect other mammals, a phenomenon called reverse zoonosis.

What’s more, wild birds can be infected with the virus, “show no signs of illness,” yet carry the disease to new areas when they migrate, said Shilo Weir, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“It’s very difficult to control pathogens when they end up in wildlife species that are free-ranging, like wild birds that have large migration patterns and interact with lots of species,” said Andrew Bowman, a veterinary epidemiologist at Ohio State University.

“Many people see pandemics as a biomedical problem, when in reality they are as much an ecological problem.”

But exactly why this latest flu evolved in a way that allowed it to be both so persistent and so deadly has eluded scientists. Whether climate change has played some role in the outbreak—perhaps influencing the pathogen’s survival in warmer, wetter environments or altering aspects of bird behavior, for example—also remains murky.

“We’re seeing changes in disease patterns with a number of different zoonotic pathogens, so I think it’s an important area where more research is needed—and specifically for avian influenza,” said the CDC’s Basler. “With climate change and deforestation, there are new opportunities for humans to interact with animals and new opportunities for disease to spread between animals and from animals to people,” he said.

“Avian flu certainly keeps me up at night,” Vora added. “It’s not a matter of if another pandemic will occur but when, and flu is one of the major concerns,” he said. “We have to strengthen our surveillance for novel flu strains and improve our vaccines and the therapeutics that we use.”

In Kalamazoo, Michigan, scientists at Zoetis—a pharmaceutical company that specializes in animal vaccinations and medicines—have been working on an avian flu vaccine for around eight years.

Recently, the company began manufacturing a version of it to be administered specifically to endangered California condors, the largest flying bird in North America. The U.S. government and partner groups quickly began a trial with the experimental shots last year after more than a dozen of the animals died from the virus in spring of 2023.

Preliminary results indicate that the vaccines can help, but only around 10% of the test animals produced enough antibodies to keep infected animals from dying, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Zoestis.

Though far from perfect, the vaccination offering is better than nothing, scientists say. But widespread rollout of the vaccine or ones like it to other wild birds, let alone mammals, still remains unlikely. The task would be herculean and create precedents that would be enormously difficult to meet in future outbreaks, Bennison says. And the U.S. government has not authorized vaccine use for any other species.

Even though avian flu outbreaks routinely lead to mass culls, vaccines may not make it to domestic poultry populations either, according to Bowman, due to global trade hurdles that make vaccination difficult. The United Nations recently acknowledged this challenge and called for changes specifically because of the global avian flu outbreak. “The rapidly evolving nature of avian influenza and changes in its patterns of spread require a review of existing prevention and control strategies,” it said in a December 2023 public statement. “All available tools must be reconsidered including vaccination.”

When it comes to stopping the steady march of this flu, even the best tools—and intentions—may fall short, Bennison said. With each leap between species, any zoonotic threat grows and amplifies the chances that it can take hold and also potentially take off among humans before it naturally burns out. Avian flu hasn’t yet been able to bind to receptors commonly found in the human upper respiratory tract, a necessary step for widespread transmission from one person to another. But if past pandemics have taught us anything, it’s that given time, viruses will evolve in novel ways.

“You can get really sad about avian influenza, but by talking about it and showing people what we’re doing to try to understand and document what’s going on, we can do justice to [other] species and try to help them,” Bennison said. It’s evident even as we try to understand this threat, he added, that humans have a role to play in staving off future outbreaks.

Such work, Vora said, must extend beyond addressing threats that may already be known to sicken humans and include other ways humans mediate spread of pathogens through our trade and travel. The spread of deadly fungal diseases, like white-nose syndrome in bats and chytridiomycosis in amphibians, for example, points to the ways that humans can serve as unwitting handmaidens for diseases that tear through other species. White-nose syndrome has killed more than six million bats, including 90% of three major species in North America in the past decade, but it’s telling where it hasn’t struck: In bat roosts inaccessible to humans, the animals have remained disease-free.

If past pandemics have taught us anything, it’s that given time, viruses will evolve in novel ways.

To prevent the spread of white-nose syndrome, travelers entering caves should wear entirely new clothes when traveling from one cave to the next and respect posted cave closures.

But to halt the spread of pandemics more broadly, larger fixes will be needed. “We have to stop deforestation, [better] regulate the wildlife trade, and improve safety when raising farm animals,” said Vora. Other steps, he added, include voting for politicians who follow science-based policy and investing in training and support for the animal- industry workforce and veterinarians.

“Many people see pandemics as a biomedical problem,” Vora said, “when in reality they are as much an ecological problem.”

Photography Assistant Delphine Brun Special Thanks Secret Atlas

This article first appeared in Atmos Volume 09: Kinship with the headline “Safe Haven.”

Bird Flu Is Spreading Quickly. What Does That Mean for Us and Other Species?