Words by Daphne Chouliarki Milner

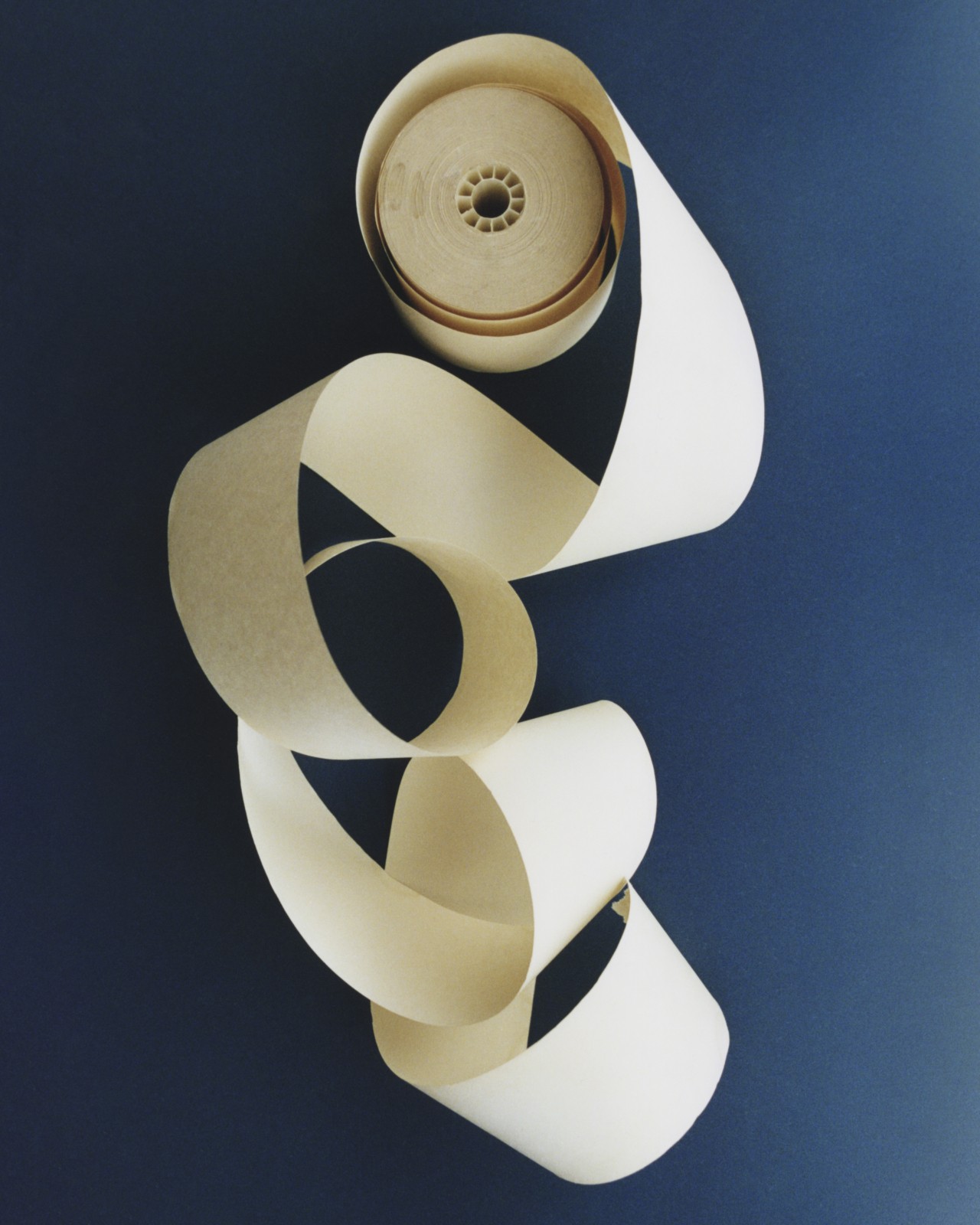

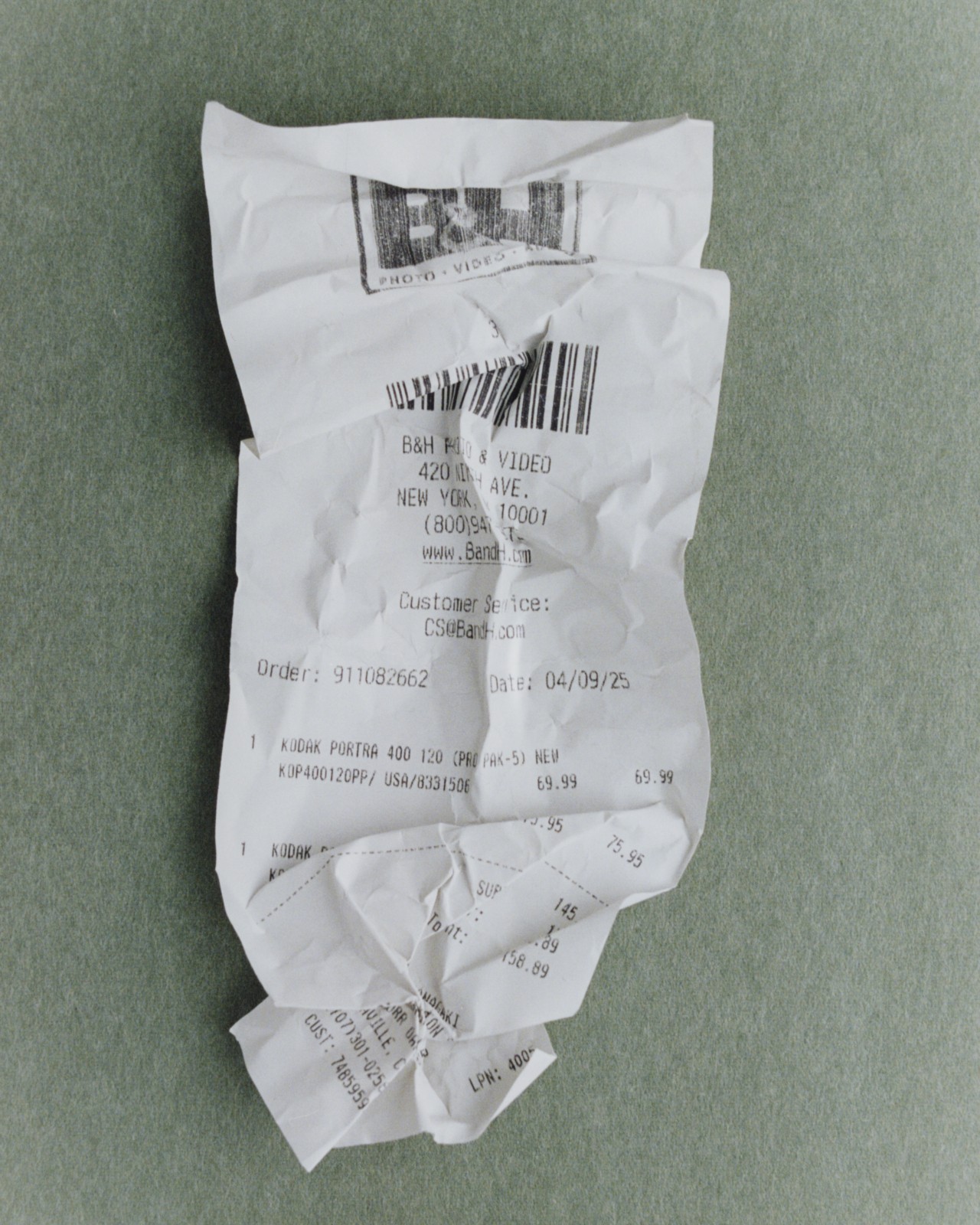

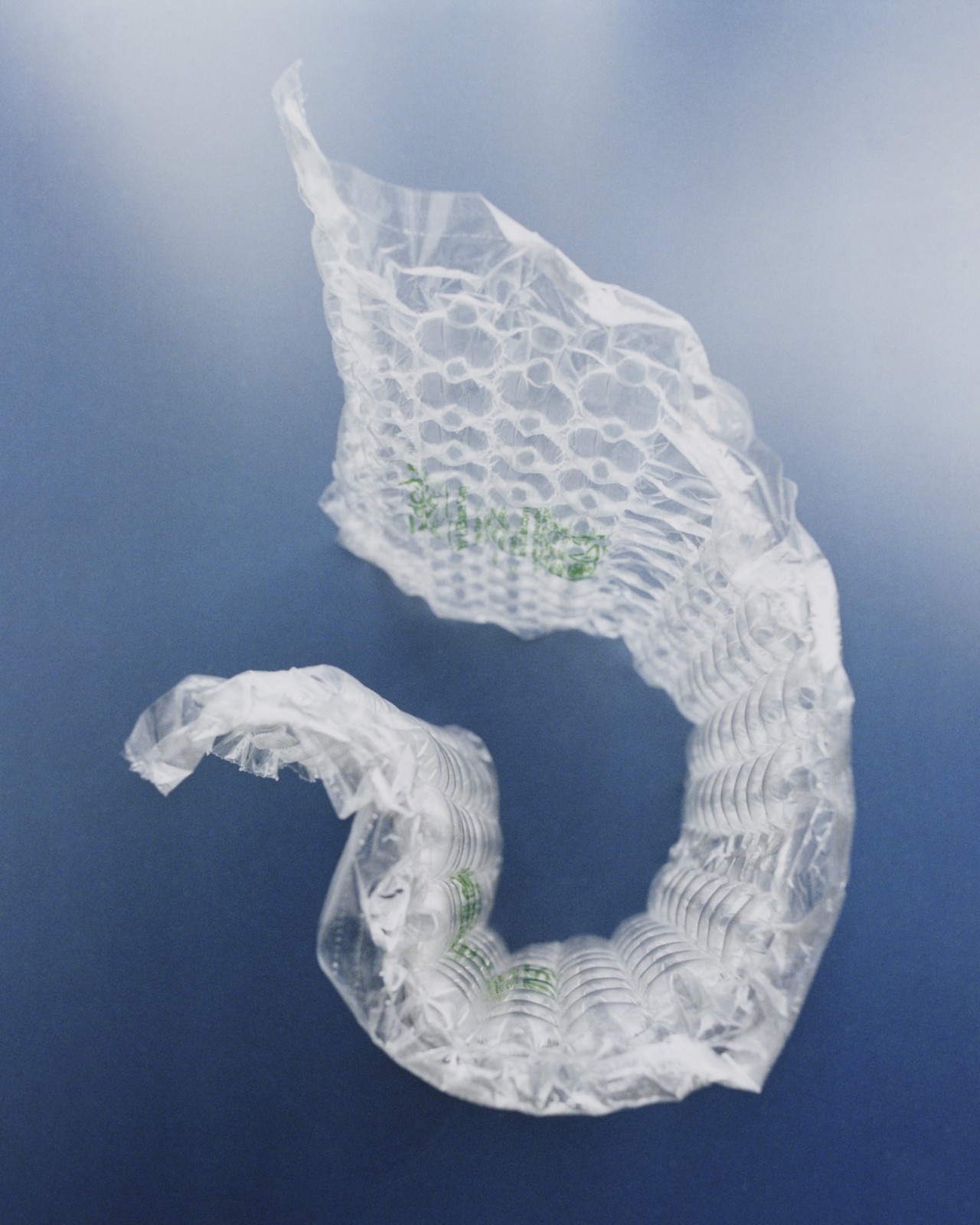

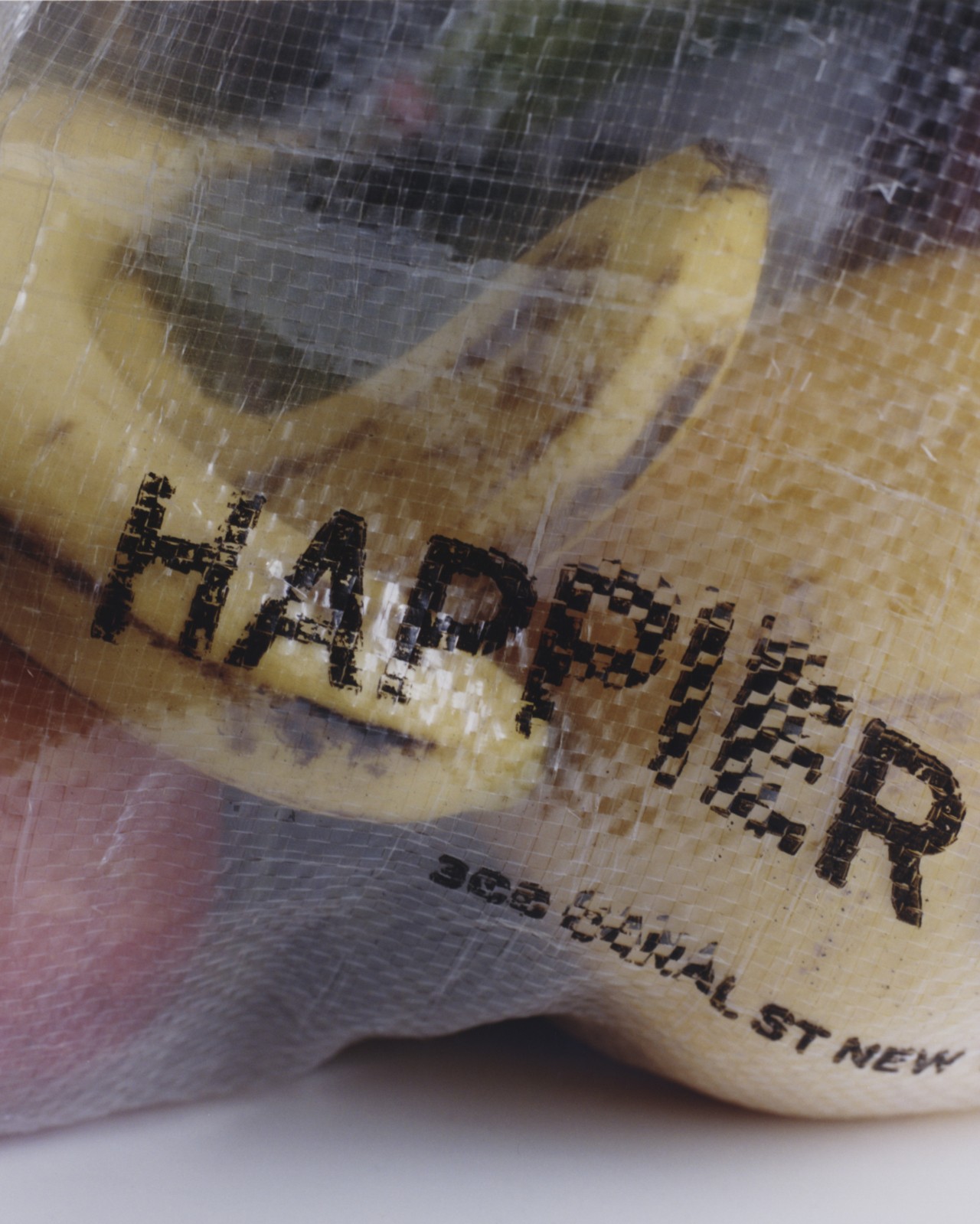

photographs by brian kanagaki

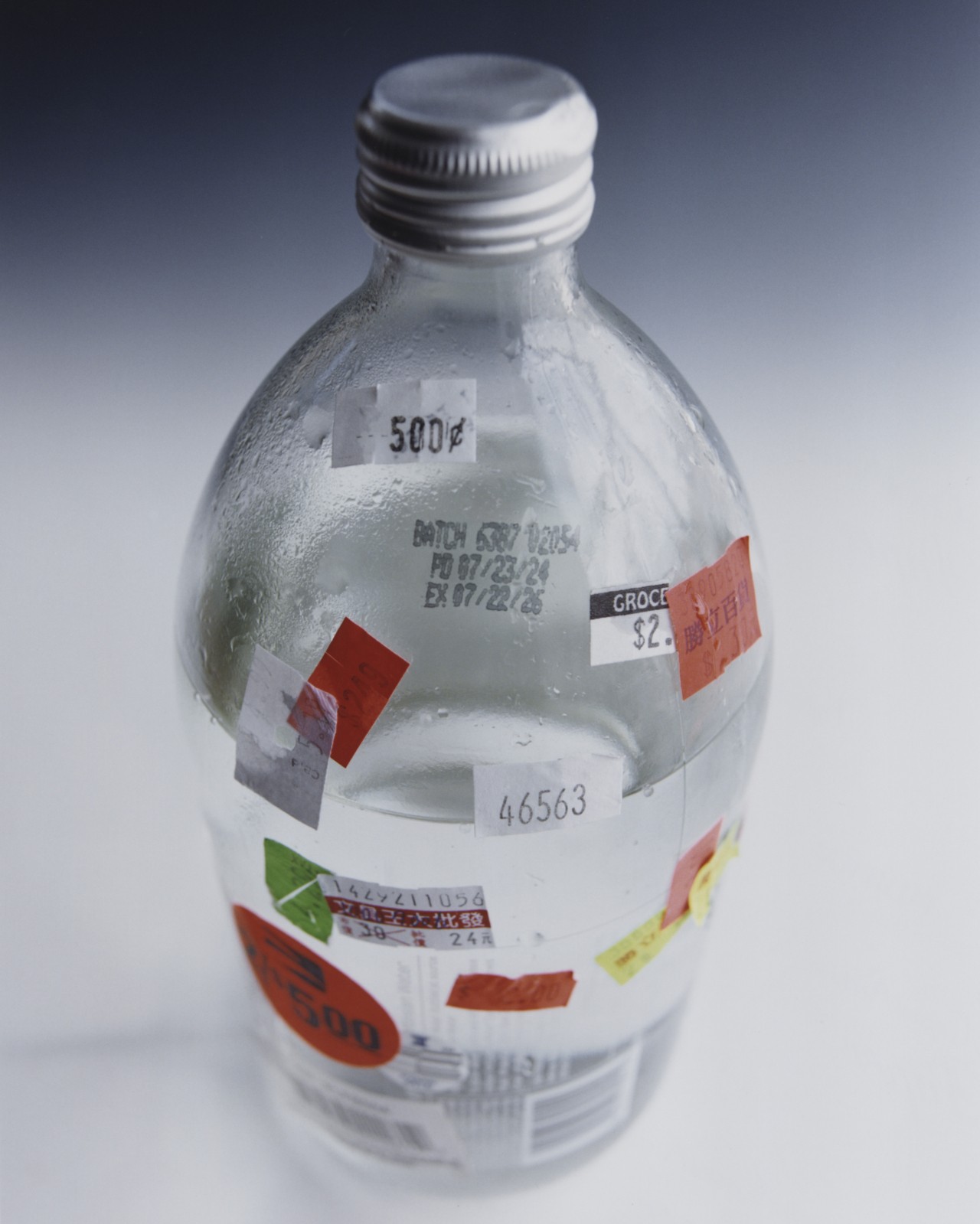

For Emily Mester, compulsive shopping was the norm growing up. Trips to the mall were routine, packages arrived at the door almost daily, and impulse buys were rarely questioned. It was what prompted her last year to write her book, American Bulk: Essays on Excess, which examines how the things we buy, amass, and discard become an intimate part of our lives—and central to our understanding of fulfillment and joy.

After years of researching consumer culture and behavioral psychology, Mester decided to embark on a three-month, no-buy period in 2024. The rules she set for herself were as straightforward as they were severe: She wasn’t allowed to buy anything online, nor was she permitted to make spontaneous purchases in stores—habits, she realized, that had once offered a reliable dose of anticipation and emotional lift. “It felt similar to when you have a crush and suddenly the crush goes away and you’re like, well, who do I dress for and who am I hoping to see when I go to this place?” Mester told Atmos. “It felt like my life lacked a carrot; it lacked something to aim towards.”

Mester’s relationship to shopping is far from unique—it’s a reflection of a culture that’s long equated consumption with contentment. We’ve been told for years by advertisers that money can buy happiness. Spend on travel, not things, the headlines say. Invest in memories. Treat yourself—you deserve it. But whether it’s a designer handbag or a getaway to a warmer climate, the underlying assumption remains the same: that joy is something we can purchase. Is that true?

New research suggests money can, to a certain degree, buy happiness depending on where and how a person lives, according to a study by the University of British Columbia. Experts found that people in wealthier countries said they gained more happiness from gifts and time-saving services, while those in lower-income nations said spending on essentials like housing and debt relief had a bigger impact. Only certain types of purchases—such as donations, experiences, and investments in personal care—consistently boosted happiness across all regions and cultures.

These findings are far from straightforward, in part because happiness is notoriously difficult to measure. It’s subjective, situational, and shaped by cultural expectations as much as by material conditions. And yet, some patterns do emerge. Professors at Harvard, University of Virginia, and University of British Columbia determined that happiness depends less on how much money we have and more on how wisely we use it in alignment with human psychology. Though buying experiences over things, helping others, savoring small pleasures can make for happier spending, the “relationship between money and happiness is surprisingly weak,” they concluded.

Happiness, it turns out, is less about what’s in our shopping cart and more about whether we spend in ways that nurture our long-term well-being.

So, how did we end up here, equating happiness with spending?

According to Professor Cathrine Jansson-Boyd, a consumer psychology expert at Anglia Ruskin University, it all started with Henry Ford. “Ford believed every American should have a car—and a cheap one,” she said. “The assembly line made that possible, and mass production took off.”

Governments quickly realized that mass manufacturing could drive rapid economic growth, cementing material consumption as a cornerstone of modern economies the world over. But the desire for possessions long predates the industrial era. “Consumption has always been around to some extent, and there’s always been an appreciation of material goods—think of the Vikings, who dyed their clothes in different colors to distinguish themselves within the hierarchy,” said Jansson-Boyd. “We’ve always been emotionally invested in things, but that interest was often tied to more practical purposes.”

Fast forward to today, and we’re deep in a “spending-happiness paradox,” also known as the Easterlin Paradox. We’ve built an economy—and a culture—around the idea that buying more will make us feel better. But psychology tells a different story: the emotional payoff of spending tends to wear off quickly, especially once our basic needs are met. A widely cited 2010 study by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton found that day-to-day emotional well-being levels off around $75,000 in annual income in the United States (adjusted for inflation, roughly $100,000 today). After that point, more money doesn’t necessarily translate to better well-being or greater fulfillment.

“When basic needs have been met, it’s not entirely clear that every additional purchase is going to lead to greater feelings of wellbeing and happiness,” said Kate Fletcher, professor of sustainability, design, and fashion systems at Manchester Metropolitan University. “There’s not a linear relationship between more stuff and well-being. But moreover, having a materialistic attitude undermines one’s sense of self in the long term. Generally, it results in people having fewer friends, and it also results in higher levels of antidepressant use.”

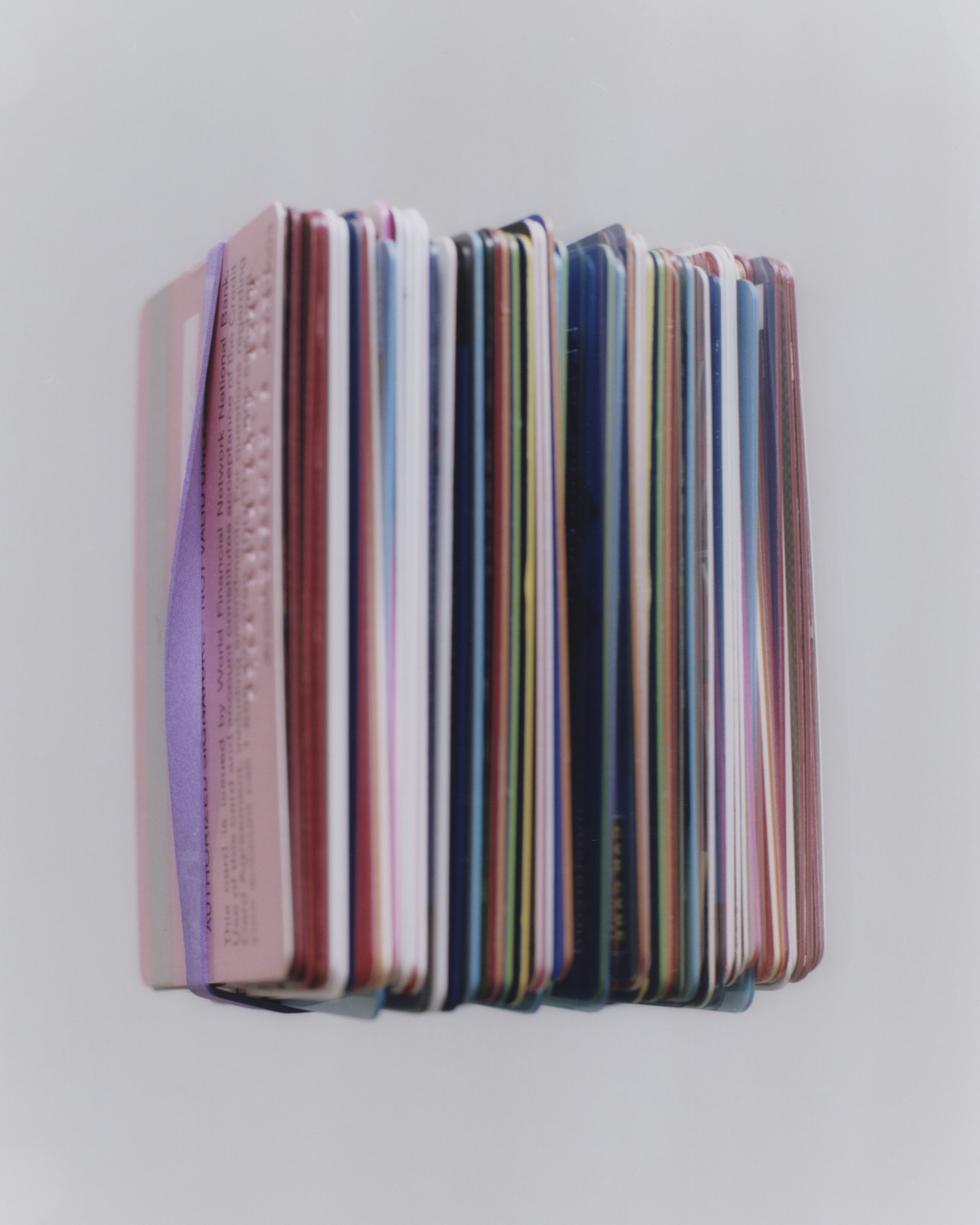

Still, in the digital age, the pressure to consume has only grown. Happiness is no longer simply sold—it’s staged, filtered, and shared across platforms where the line between advertising and everyday life has grown increasingly blurry. A quick scroll through Instagram or TikTok reveals the shift: Brands now sell aspiration through products. “What’s driving overconsumption on social media is this culture of upward comparison,” said Jansson-Boyd. “It’s as if we’re all on a hamster wheel,” she added. “It spins faster and faster and faster and faster, and we need more and more things to feel better. It’s like a drug addiction; Unless you up the dose every time it’s not working.”

Our shopping habits don’t come cheap—neither for our mental nor planetary health.

Compulsive shopping is linked to anxiety and low self-esteem. The more we measure our lives against photoshopped perfection online, the more we feel we’re falling short—and the more we spend to make up the difference. In the process, we take a bigger toll on the planet.

Fashion alone accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions, around the same as what’s generated by the European Union, even as the average garment is worn just seven times before being discarded. “It’s been more than 30 years of sustained work to try to address the social and environmental inequities within the fashion space—especially as our spending intensified,” said Fletcher. “But what we see from the statistics is that the impacts are getting worse, not better.”

And yet, the cycle continues. Consumption is still treated as a sign of success, and growth as the measure of economic health. Slowing down—whether personally or systemically—can feel like failure. “We are continuously conditioned, especially through politics, to believe that consumption is really fundamental because that’s how the world goes around now, whether we like it or not,” said Jansson-Boyd. “This is really worrying because if you are coming from a sustainable consumption perspective, we are just not slowing down. And we are ruining the planet in [our pursuit of stuff].”

But what if we stopped buying into the illusion that consumption is a necessary part of fulfillment? After three months of no new purchases, Mester was forced to find new ways to fill the emotional space that shopping once occupied. “I would say gardening had a greater impact on my overall happiness, which I was shocked about because I’m not a particularly Earthy person,” Mester said. “I found that there are many more ways to recreate the joy, and the pleasure of noticing and obsessing and deliberating and discovering ourselves, in ways that aren’t shopping.”

Mester may be onto something. Research increasingly shows that non-material experiences—like time in nature, volunteering, making art, or spending time with friends—are longer-lasting sources of happiness. In a study published in The Journal of Positive Psychology in 2016, participants who engaged in “everyday creative activities” reported greater life satisfaction and emotional well-being.

This reorientation toward meaning over materialism is beginning to take root elsewhere, too. Across social media, no-buy challenges like the one Mester participated in attract growing communities of followers committed to resisting overconsumption. Meanwhile, degrowth movements are gaining momentum as activists, scholars, and policymakers question the sustainability of endless economic expansion. Some countries are even beginning to rethink what progress means altogether, shifting their focus from gross domestic product to gross domestic happiness. Bhutan famously pioneered this approach with its Gross National Happiness index, and more recently, governments in New Zealand, Iceland, and Scotland have adopted well-being budgets that prioritize health, equity, and environmental sustainability over traditional economic growth.

“Those are the things that give me the most hope,” said Fletcher. “Ultimately, the transition period that we’re in is going to be highly impactful for industry bottom lines. It cannot be otherwise. The sector will have to shrink in order to sit within planetary boundaries, and there’s going to be an almighty resistance to that. There already is.”

What We Lose When We Spend to Feel Better