WORDS BY JASMINE HARDY

photographs by clarence williams

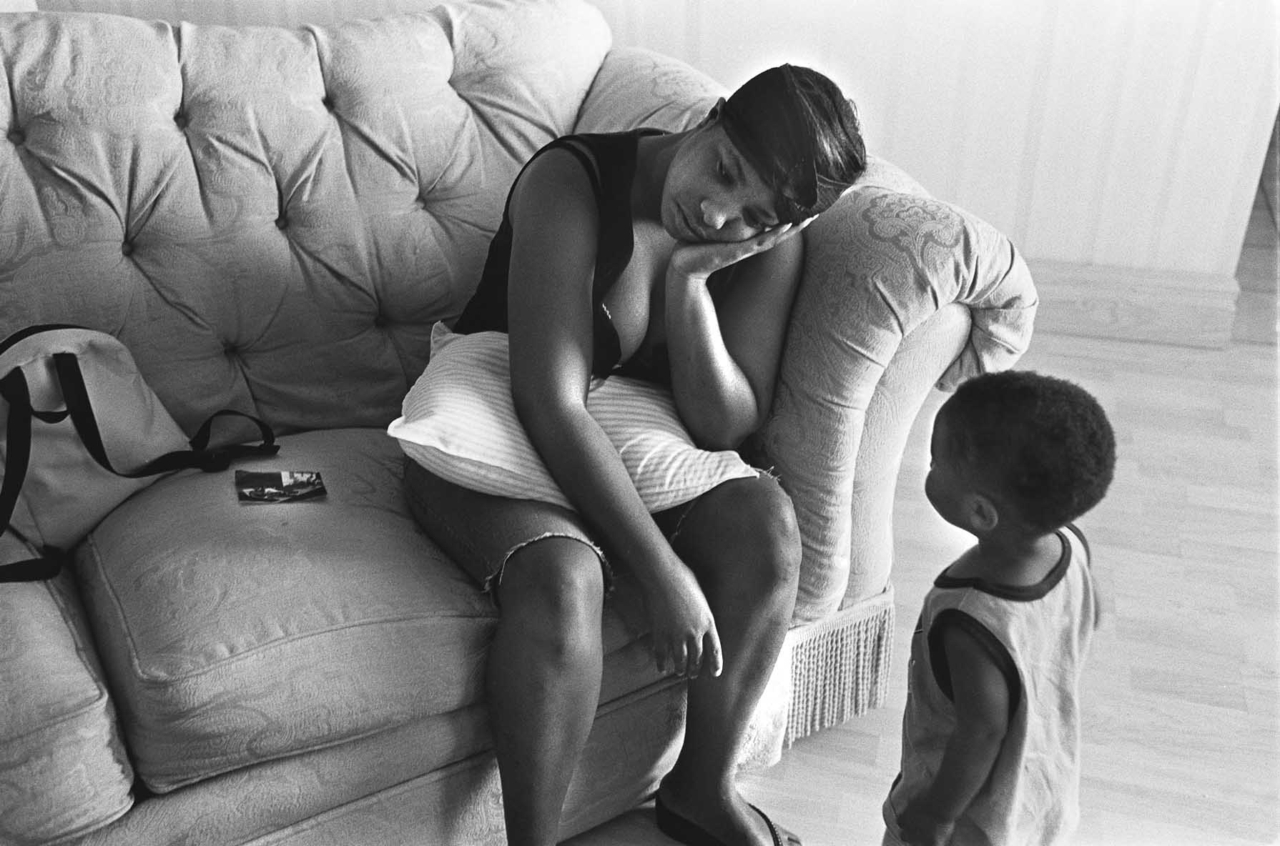

Twenty years ago, photojournalist Clarence Williams survived Hurricane Katrina—one of the deadliest storms ever to hit the United States—as floodwaters swallowed his uncle’s New Orleans home. The storm devastated the city, killed nearly 2,000 people, and led to the largest climate-related mass migration in the United States since the 1930s. Whole neighborhoods remained uninhabitable for years, and the recovery became one of the most expensive and protracted rebuilding efforts in American history.

For Williams, remembering Katrina means holding onto the ironically comedic moments that helped him cope: the struggle of trying to rescue his family’s stubborn cat, all of his family’s bottoms getting wet as their house flooded. He approaches life with love and humor, and that same positive disposition drove him to use his camera to document the destruction in New Orleans, as well as the resilience and community that emerged during the recovery. It was this outlook that earned the trust of people who had lost everything and allowed them to share their stories with him.

Today, his photographs from that time are collected in a series titled Katrina 20, now on view at the InLiquid Gallery in Philadelphia through September 27 to mark the hurricane’s anniversary. The images chronicle moments of love, disparity, and hope through the lens of someone who experienced the disaster firsthand. On this milestone, Williams speaks with Atmos about what it means to document a pivotal moment in history and why his journalistic philosophy has always been guided by a “love ethic.”

Jasmine Hardy

Could you first take us back to the day of Hurricane Katrina and share your lived experience of it?

Clarence Williams

It was me, my uncle, his girlfriend, and her 83-year-old mother. The night before, we watched Ray, drank Red Stripe, ate crabs, and had a wonderful evening. I woke up the next morning and it was raining so hard. I remember looking out of the window, being like, What is going on?

I looked at the storm door and you could see the water slowly rising up. I was like, Yo Unc, look at this. As soon as that came out of my mouth, water just started coming in from every direction—through the walls, through the windows. We were standing there and [water hit] our toes, our ankles, our forelegs, our knees. It was just rising, rising, rising.

It was rising so rapidly we all had to scramble into the attic where we spent the night. In the morning, my uncle and I got out of the attic, swam through the house to the outside, climbed up on the roof, where you could hear people yelling all over. We were screaming, screaming, screaming, screaming. And at that point it was just nothing. That day came and went. [Then,] we went back down through the water into the attic to sleep another night. It was either the second or the third day when we started to see helicopters.

“Even in the worst of times, if you approach people with love, they’ll let you tell their stories. And so my guiding principle has always been to approach everyone with love and with honesty.”

[Throughout those days], we listened to our wind-up radio. And the news kept talking about New Orleans refugees. I thought to myself, what are they talking about? Then I realized: These crazy bastards are calling me a refugee. I was like, I was born [here]. I ain’t no refugee.

I’m a journalist, so I knew that language was so careless. If they really wanted to be specific about those folks who were on roofs and didn’t have any place to go—those that were at the Superdome, the Convention Center, all of these places—the proper term is internally displaced person or IDP.

I think we did four days on the roof, three nights in the attic. Eventually, the [two women] were picked up in a Coast Guard bucket. A couple of hours later, an army helicopter hovered above the house, and [my uncle and I] ran and got on it. They told me I couldn’t bring anything onto the helicopter. But I was like, I can’t go without my [camera] gear. I was seeing so much, but I didn’t have any film [to photograph it].

Jasmine

Your photo series spans 13 years after the hurricane. You were visiting family when Katrina hit, but what made you decide to stay?

Clarence

The city was very empty for a long time. About a month after Katrina, I remember being in a bar on Frenchman Street one night; it was me, the bartender, and these two white guys. They were having a conversation. I was sitting next to them when I heard, “New Orleans is so much better now that all the n*****s are gone.” I whispered, “Well, I don’t have a lot of means, but I do have a little. I am moving here.” That very moment, that’s when this became my home.

Jasmine

Could you speak to how the community and landscape shifted in the years after the storm?

Clarence

It was slow. You could tell who had resources; who had a sense of savvy to deal with the insurance, the government. You could tell which pockets of the city were under-resourced—drastically under-resourced. As in so many places now, but especially because the city was such a clean slate [after the storm], the winds of gentrification were intense. You could [actually watch] gentrification happen because so many folks who came to help, myself included, stayed. The rebuilding of the city also changed it.

Jasmine

What was your approach to documenting these rebuilding efforts, particularly in the communities trying to do so with such few resources?

Clarence

It’s the way I’ve approached everything. This is my journalistic philosophy: Even in the worst of times, if you approach people with love, they’ll let you tell their stories. And so my guiding principle has always been to approach everyone with love and with honesty. At the tender age of 58, I am truly dedicated to living [what I call] a love ethic.

I look at it as my beginnings as a journalist. Even though I didn’t know how to describe my approach, I was photographing from the perspective of a love ethic. Now, I’m like, “Oh, I can expand this to everything in my life.” I’m an oddball—it’s made me a weirdo. But I have no choice but to live this way.

Jasmine

What do you make of your role as a photojournalist, rather than a photographer, documenting that particular time in history?

Clarence

I’m not just reporting what I see, I also have a point of view. [That comes through in] what I am choosing to share. It’s not a matter of being blindly objective. I was there, and I want you—the viewer—to see what I saw. For example, [in the series] there’s a picture of a dead body on a corner with a guy in a brand-new car in the background.

We need to really look at that. You could say, This dude is not even in a body bag, and this cat in the back is in a brand-new car. That’s really wild. I titled that picture “Disparity” because it’s a good example of [the stark divide in] income at the time of the storm. Now, we’re living through another moment where income disparity is right in front of us.

Jasmine

There’s a photograph in your series of two men walking through debris scattered with discarded prison uniforms right next to a prison. It really struck me because it speaks to something I often think about: how the most vulnerable people are so often abandoned in these kinds of disasters.

Clarence

I see it like this: If [the country] is going to abandon its taxpayers, then it’s definitely going to abandon those who don’t pay taxes. I have been to different countries, through different famines and wars, and I’ve seen how quickly thousands of people can be mobilized. I remember thinking [during Katrina], What is taking them so long? I’ve watched this country move mountains across seas, [but at home the response stalled]. And if a disaster like that struck today, I’m not betting on our administration to come through any faster.

“I’m not just reporting what I see, I also have a point of view…It’s not a matter of being blindly objective. I was there, and I want you—the viewer—to see what I saw.”

Jasmine

Do you think the current government’s response—or lack thereof—would be any different from what we saw in New Orleans 20 years ago?

Clarence

No, but for different reasons. Back then, I felt the inaction was, simply put, because we were Black. Today, I think it would come down to institutional incompetence. Different reason, but same result.

Jasmine

Your work is on display in a couple of galleries for the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. As someone who lived through the storm, what does the commemoration mean to you personally?

Clarence

This morning, my neighbor said, “Clarence, I don’t know about all this celebrating.” I was like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. Ain’t nobody celebrating. For me, I’m just remembering. I want people to remember.”

And that’s really what it is for me—this opportunity to remember. I think it’s important to remember Katrina because it was a pivotal moment in modern history and it really changed the way I feel about this country. Historically, [this nation] doesn’t always acknowledge events like that—but those of us who lived through it know: We built it.

Jasmine

Do you have any advice for other photojournalists on how to responsibly depict the most vulnerable communities, especially as these sort of large-scale climate disasters become more frequent?

Clarence

Four things: Be honest. Be gentle. Be loving. And be committed to telling their stories.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been condensed and edited for purposes of length and clarity.

This Hurricane Katrina Survivor Depicted Life After the Storm