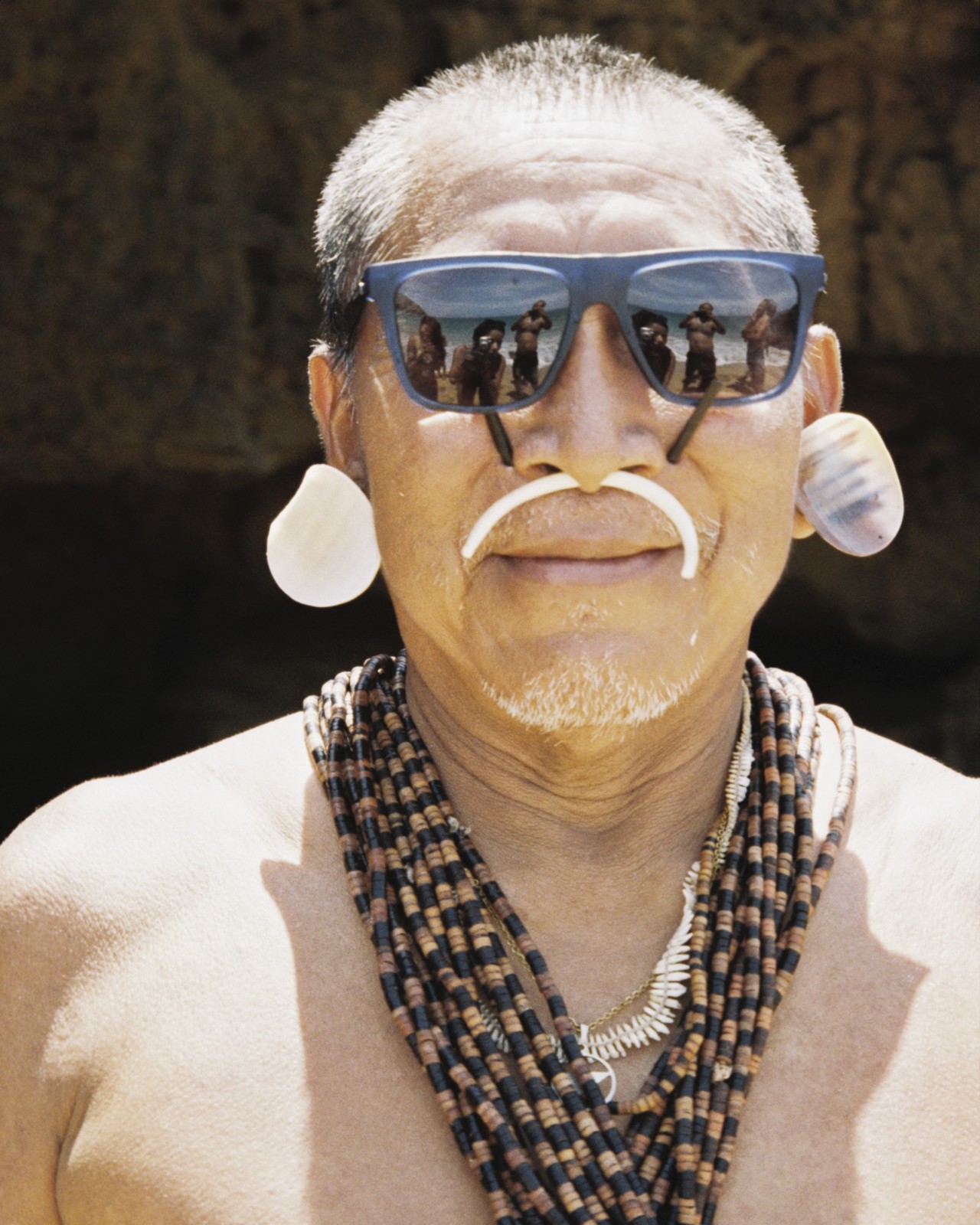

Michael Guetio, painter and tattoo artist from the Nasa people of Cauca, Colombia

Words and photographs by Nina Gualinga

“Every tattoo, every scar is a recognition that we’re still here, that they did not kill us.”

— David Hernández Palmar, Wayuu co-founder of Asho’ojushi collective and organizer of Tattooed With Thorns

Across continents and centuries, Indigenous peoples—from the Inuit of the Arctic to the Māori of Aotearoa and the Matis of the Amazon—have inscribed their identities onto their bodies. These markings, whether inked into skin or painted with plants like Jagua (also known as Wituk or Jenipapo), are more than ornamentation. They are living testaments to a profound relationship with the land: personal, collective, and ancestral.

Colonization, however, attempted to sever these ties. Generations of Indigenous people have suffered under forced assimilation policies, erasing traditional practices and stories in the process. Today, the scars remain—across landscapes ravaged by oil extraction, mining, and deforestation, but also on the bodies of those still fighting against the ongoing stigma and discrimination for wearing our cultural markings.

Tatuado Con Espinas, or Tattooed With Thorns, is an attempt to heal these wounds. Since 2019, the collective Asho’ojushi has worked collaboratively across research, creative work, and on-the-ground organizing to bring communities with ancestral tattoos together and produce communicative and educational materials about body art for Wayuu communities and beyond. Tatuado Con Espinas is restoring pride in what the body has always known: that to mark the body is to carry the territory within us; and that the land lives within us wherever we go.

For Indigenous peoples, the land is not divided by borders. The traditional territory of the Wayuu people, for instance, spans Colombia and Venezuela, reaching toward the Caribbean coast, and serves as a reminder that cultural and ecological continuity long predates modern nation-states. It was in La Guajira, the ancestral territory of the Wayuu people, that Tatuado con Espinas held the world’s first global ancestral tattoo gathering. There, near the Colombia-Venezuela border, Indigenous artists and knowledge-keepers from the Amazon, Arctic, Pacific, Mesoamerica, and beyond came together in a collective act of resistance and restoration—one inked into skin, memory, and place.

What does tattooing mean to you and your people?

Among the Wayuu people, tattooing is a way to go beyond this realm—to Jepira, the place where the souls of our dead Wayujos rest.

There was [a time when] many of our traditions were banned, such as tattooing, and even dancing. But I believe that if you stop dancing, you also forget part of who you are as an Indigenous person. So reviving tattooing from childhood is an exercise to strengthen our identity. Because when we forget our practices, we also forget how to take care of the territory.

The tattoo allows you to always remember where you come from and what your path is in this realm.

Can you tell us more about symbolism and markings?

Everything is related. The symbols we use reflect our surroundings. You don’t just tattoo anything. First, you tattoo your clan. There are many Wayuu clans, and each clan has a different design that makes it known, this Wayuu mark is from that place. It is what you take with you to the afterlife, to Jepira. It is often the first tattoo you receive.

There are other forms, too, like tattoos given for spiritual protection, when you are given your tattoos through dreams for protection. There is a connection between the protection of the territory and the protection of yourself. Because, when you protect yourself, you protect the territory. So, by practicing self-care, you are also participating in the care of your territory.

What has this gathering meant to you?

It has shown me that it’s not only the Wayuu people who are going through this process of reclaiming our traditions, culture, and what it means to be Indigenous. [Tatuado Con Espinas] has allowed me to see firsthand that other Indigenous peoples are going through the same process. And that makes me feel accompanied—not only in Abya Yala (Americas), but around the world.

How did your pathway into painting with Jagua start?

I started because I saw that my people’s cultural practices were being lost. We live in a relocated community—my parents, grandparents, everyone was displaced when the government began to build a hydroelectric plant. They were dispossessed of our traditional lands and relocated against their will to the place where we live now; a place that was already devastated. There were campesino communities there, and my people, as Indigenous people, started experiencing discrimination.

For the first time ever, my parents came to know what depression is. In an effort to protect future generations, they made the decision to stop speaking our language, stop painting our bodies, and stop practicing our traditions. So, when my generation was born, we did not know much. Only that we were Indigenous.

But I became curious. I started asking about the symbols and learned they weren’t just aesthetic. They carry spiritual meaning and the very identity of our people. Each symbol represents something living: an animal, a river, a mountain, a plant. And all of these also represent spirits that guide our people through the shamans.

So, I began to use the [body] paint as a form of resistance—against the racism that Indigenous people suffer. It [became a way to show] pride and to understand that there was no reason to feel ashamed of who we are. My dream has always been that what I do helps the following generations continue this forward. Our identity is a part of our territory. We take it with us wherever we go. To wear it with pride is how it should be—not just as fashion, but as a culture that is lived and loved. That has been my path.

“It is what you take with you to the afterlife, to Jepira, because it is the first tattoo you get on your skin. And the tattoo allows you to always remember where you come from and what your path is in this realm.”

Can you tell me more about how the patterns and paintings connect to the territory?

In my culture, it is said that every being has a soul—the trees, the water—and that they feel just as we do. We have to treat them with respect, not as a potential source of income. Many see a forest as profit. For us, it is much more than that.

Our paintings show that we can come to love and respect what we have around us. The patterns represent our connection with what surrounds us; a reminder that, in the end, we are not the owners of the land. We are its protectors. This benefits everyone—not only my community, but everyone. When we protect the forest, we are even helping the people who are cutting down and destroying its trees.

These markings connect us to all our Indigenous brothers and sisters from across the world. We have a united vision: To protect the forests, and everything that lives within them.

Who wears the Māori tattoos and why?

Predominantly, the puhoro body suits [full-body tattoos] were worn by warriors. They showed status—particularly in battle. But in this day and age, people wear them to connect to their heritage, to tell their stories. Getting a full-body tattoo isn’t easy. They’re not made for the faint of heart.

My sister, for example, wanted her baby to come into the world seeing the patterns—and growing inside the stories that live on our skin. When you carry these designs on your hips, they give you strength. They connect us to our Taiao: the world, the Earth and our surroundings. So, to live with these [patterns] every day, that are engraved into your skin, creates a pretty strong connection. And when the baby is born, you can see those walls of patterns—it becomes a place of safety and renewal.

What has your experience been as an Indigenous tattoo artist in today’s society?

It started when I was a child. I grew up with stories about how our world evolved. Our myths and legends shaped my outlook on life, which I’m really grateful for.

I started my apprenticeship when I was 21 years old. But there was a Western system in place and the protocols didn’t exactly align with ours. I had to navigate that—fitting into that Western mold, while holding onto what was in my heart. That’s what so many cultures have had to do. Whether with ceremonies, festivals, or other traditions, we’ve had to adapt to the rules that have been imposed on us. There was a time when Māori tattooing was taken from us. So there had to be a revival. And who led that revival? Māori did.

What are the Maori tattoo symbolism based on?

There are so many symbols, but usually they are based on your Taiao; the Earth. If you live in a bushland, your tattoos might reflect that.

The way that the ancient used to practice body tattooing was collectively by going to a meeting house. It has never been about the individual. That sense of individualism came later because, again, colonization.

So if you’re from a different area, the markings will reflect that?

Yes. [The tattoo] will then reflect the story of that area, and carry a direct link to who you are, where you come from, and where you’re headed. It’s about your identity. For a lot of people, [as the tattooing process unfolds], they start to look more like themselves. And we always say, “Now you look like you.”

What did you take away from the gathering in Wayuu territory?

It was powerful to see everybody be their true selves—being your Indigenous self without having to explain it. That was really beautiful.

Your tattoos hold a lot of Nasa symbolism. Did the Nasa people traditionally have tattoos?

Some elders tell me that we did. But my learning is still very young; I have only been learning for about seven years. I think some regions may have practiced tattooing, others may not have.

What do the symbols mean to you?

Our sacred sites and stones carry carvings that tell our story of origin. During times of ritual, we, the Nasas, salute these places. Our traditional doctors perform offerings—what we call “the brindis“—to this hill or that hill, and to those sacred stones. As Nasa people, we learn to geo-reference where these sacred sites are. Even if you are 1,000 kilometers away, you already know where the sacred sites are.

In other words, it is also through the symbols that you know how to locate yourself; know where you are in the territory?

Yes, I recognize the symbols of my territory and also those of the surrounding territories.

What awakened your interest in the symbolism of your people? How did you get into painting and tattooing?

When I was little, my uncle used to go to town once a week. He would leave at 2 in the morning with his horses to sell coffee and whatever else we had, only to arrive in town by 8. He always brought a newspaper back and a little piece of a comic book. I waited happily every week—that’s how my love for drawing began.

At the time, the only things that reached our community were armed groups or evangelical campaigns. One day, one of the commanders of the guerilla told my dad they’d recruit me and take me away when I turned 15 or 16 years old. To protect me, my dad sent me to the city when I was 11. I ended up in the town of Popayán, a very racist town. It was a shock to leave my community. At school, I remember being beaten and having my notebooks torn apart.

That’s where I realized I was alone. The racism made me feel like I could no longer look people in the eye. During my teenage years, I wasn’t able to speak to people who weren’t from my community. All I did was draw.

“The appropriation of our symbols—they are the last thing they can take from us. Let’s put it that way. Because they have already tried to take everything else.”

Then one day on my way to school, I saw a chiva—a bus—pass by. People were waving their colorful scarves. I immediately felt I could relate to them and thought, Who are these people? I asked my dad: “We are Indigenous and we belong to a cabildo (Indigenous organization); we belong to a resguardo (Indigenous territory).” That’s when everything changed. I realized that everyone was the same as me; I felt strengthened and I kept drawing. I wanted to do things that would continue to strengthen me. I still experienced a lot of racism, but I was no longer interested in validation from the outside world. I was more interested in my community.

I also practiced medicine from a very young age. It was beautiful—our spiritual guide said to me, “You have to start tattooing. You are good at it.” At first, he told me to do just five marks. As time went on, he said, “Do another five, do some research.” It became a kind of test. I would return to him, and he’d ask “What did you learn?” I would show him and sometimes he would correct me—“That is not what it means.”—and he would teach me again. Now, he tells me, “I no longer have anything to teach you.”

What are your thoughts on the use of Indigenous symbolism and cultural appropriation?

The appropriation of our symbols—they are the last thing they can take from us. Let’s put it that way. Because they have already tried to take everything else.

What has this gathering meant to you?

I am leaving this gathering feeling inspired; [inspired] to return to my community, to speak more with our elders, to weave more. I think that this event, for me as well as for all the comrades, gives us strength. A reminder to continue to keep reclaiming ourselves and keep betting on our own paths.

My dad always told me: “You can be whatever you want. But never forget where you come from.”

Can you share a little about the Asho'ojush collective?

Indigenous peoples are coming together—each of us standing at a unique moment in the reawakening of our ancestral tattoos.

This is not just a moment; it is part of a larger, long-term effort. The Asho’ojushi initiative is a macro-project that includes community gatherings, intergenerational workshops, impact tours, and the creation of the documentary Searching for the Marks of the Asho’ojushi, directed by David Hernández Palmar and Marbel Vanegas, and produced by Jona Luna and Leiqui Uriana.

What do ancestral tattoos represent for Indigenous peoples today?

We are witnessing how new generations are reclaiming iconographies and their metaphors, turning them into sources of certainty, healing, and pride for our peoples.

Some communities have had their markings dormant for 40, 100, even 300 years. Yet today, the tattoos are vibrating once again on our skins, resonating with memories of the land. They remind us that these visual narratives are not merely symbolic. They are integral to how we defend and sustain life in our territories.

Editor’s Note: Interviews have been condensed and edited for purposes of length and clarity.

The Land Engraved in Our Skin