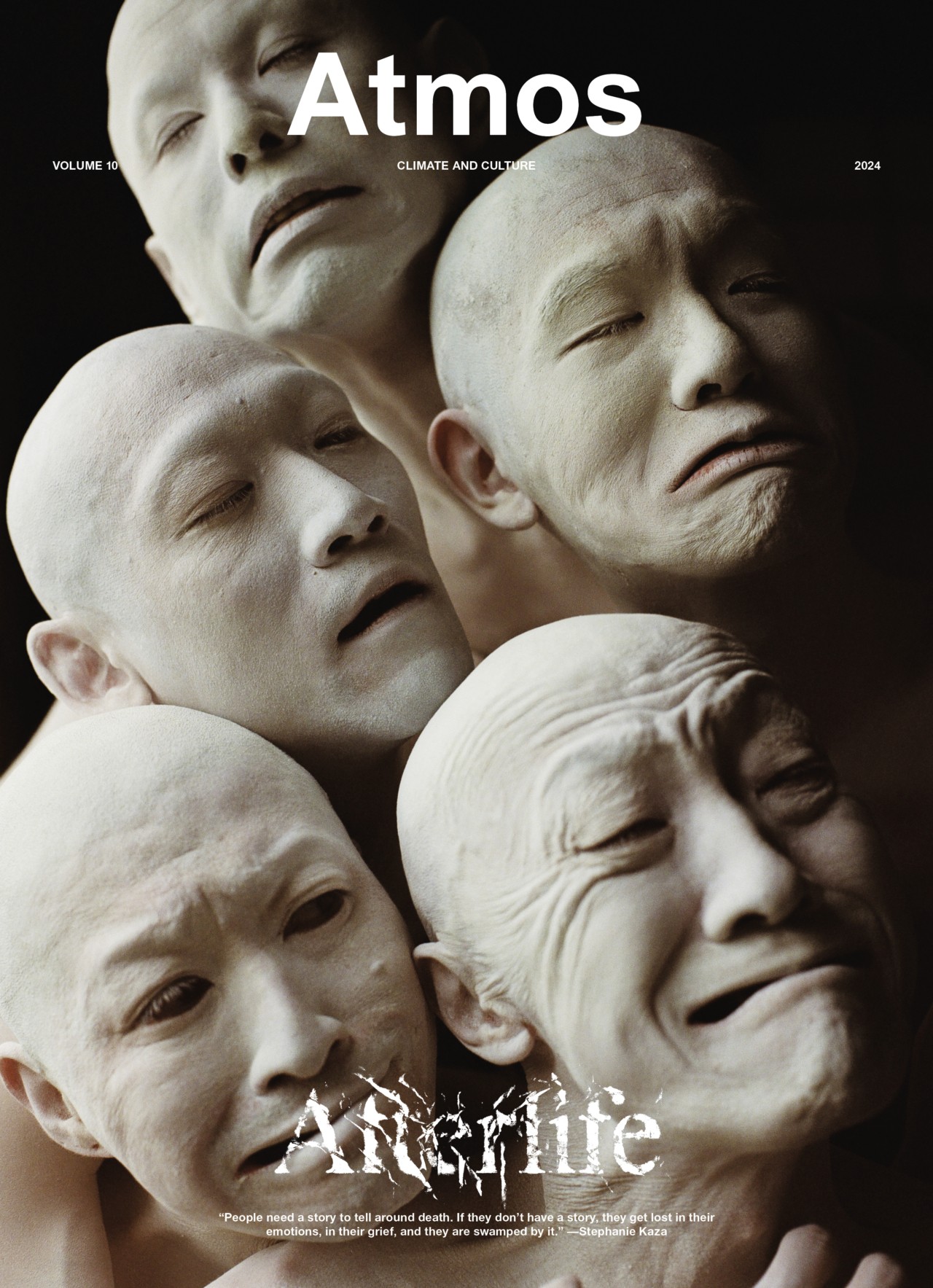

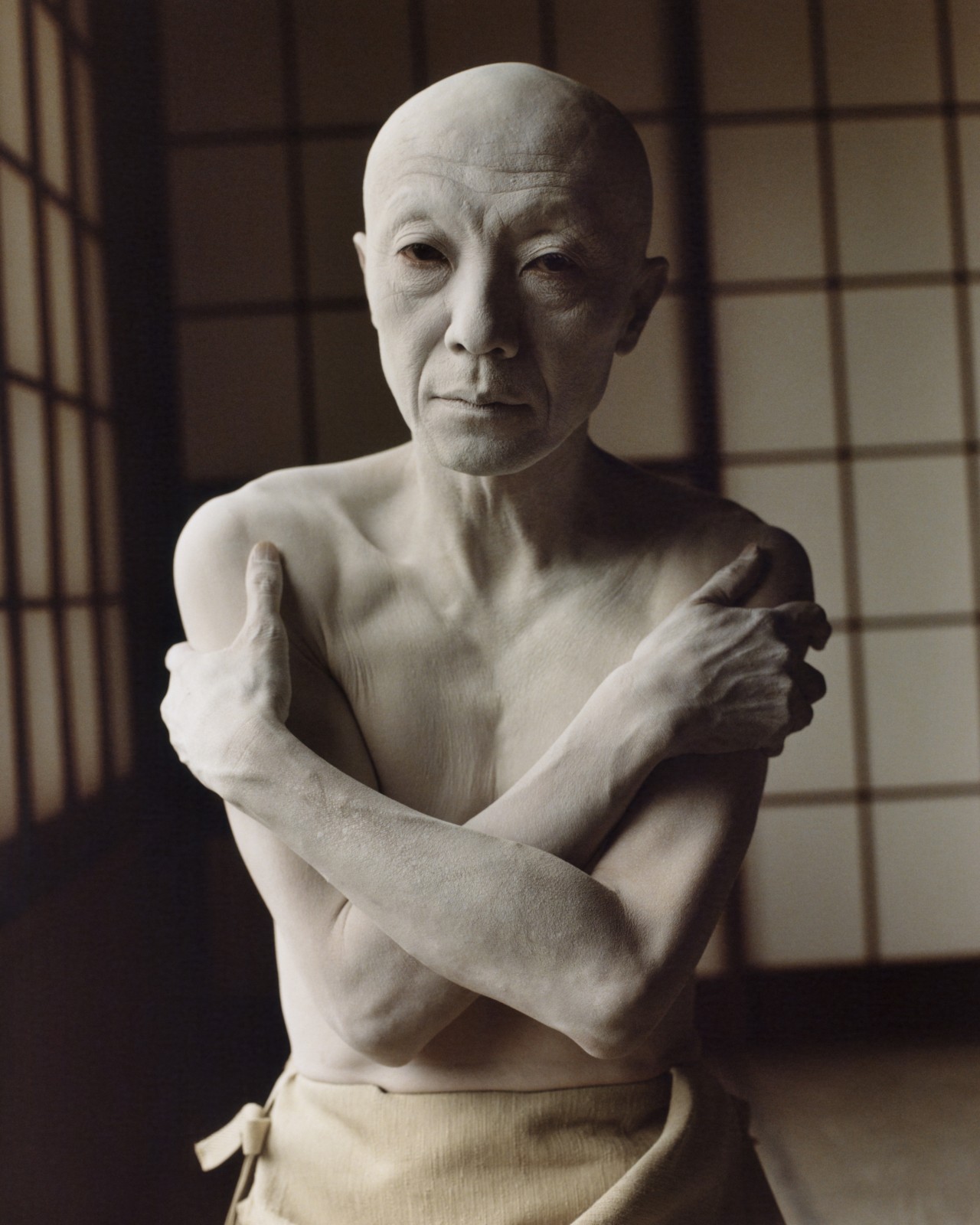

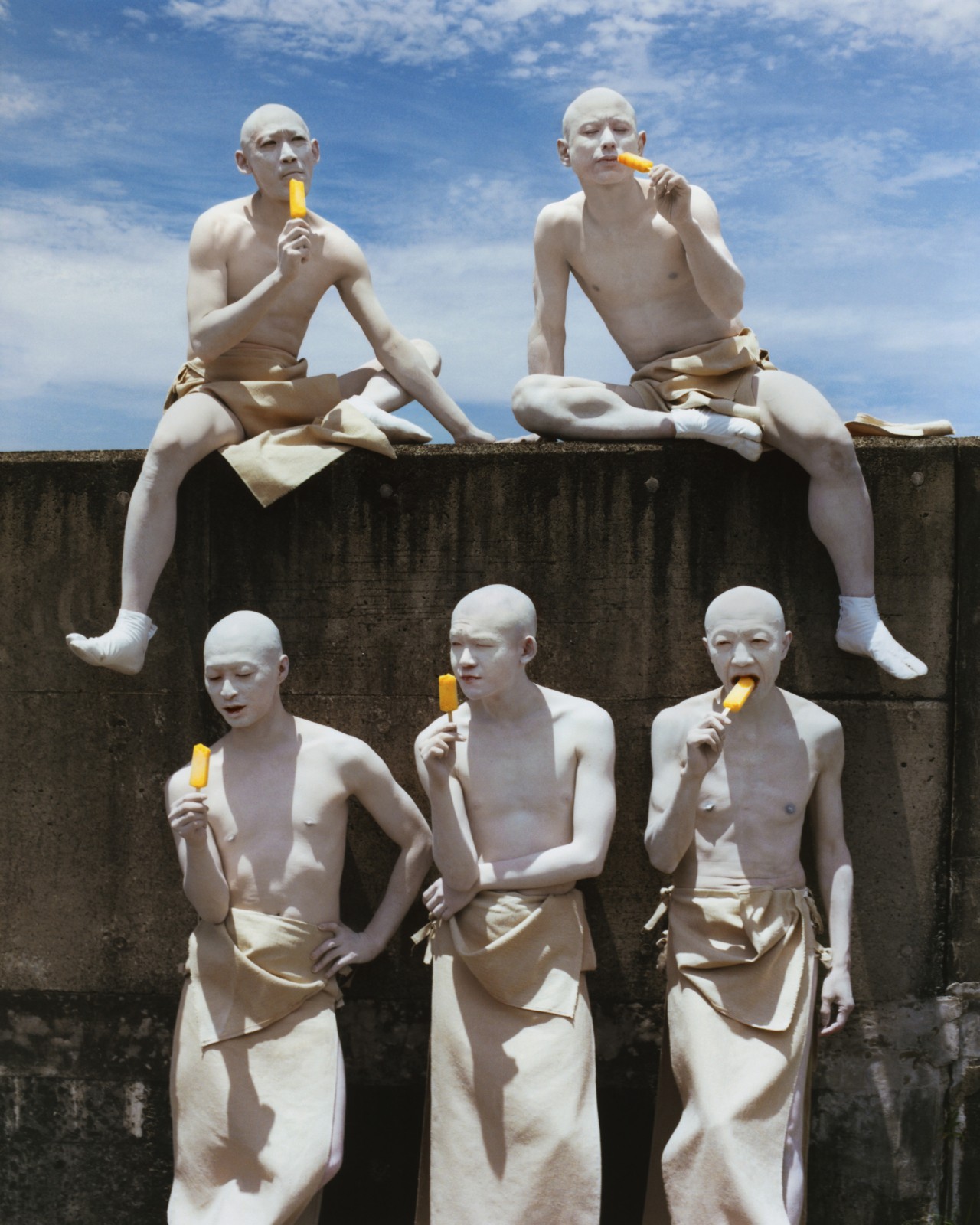

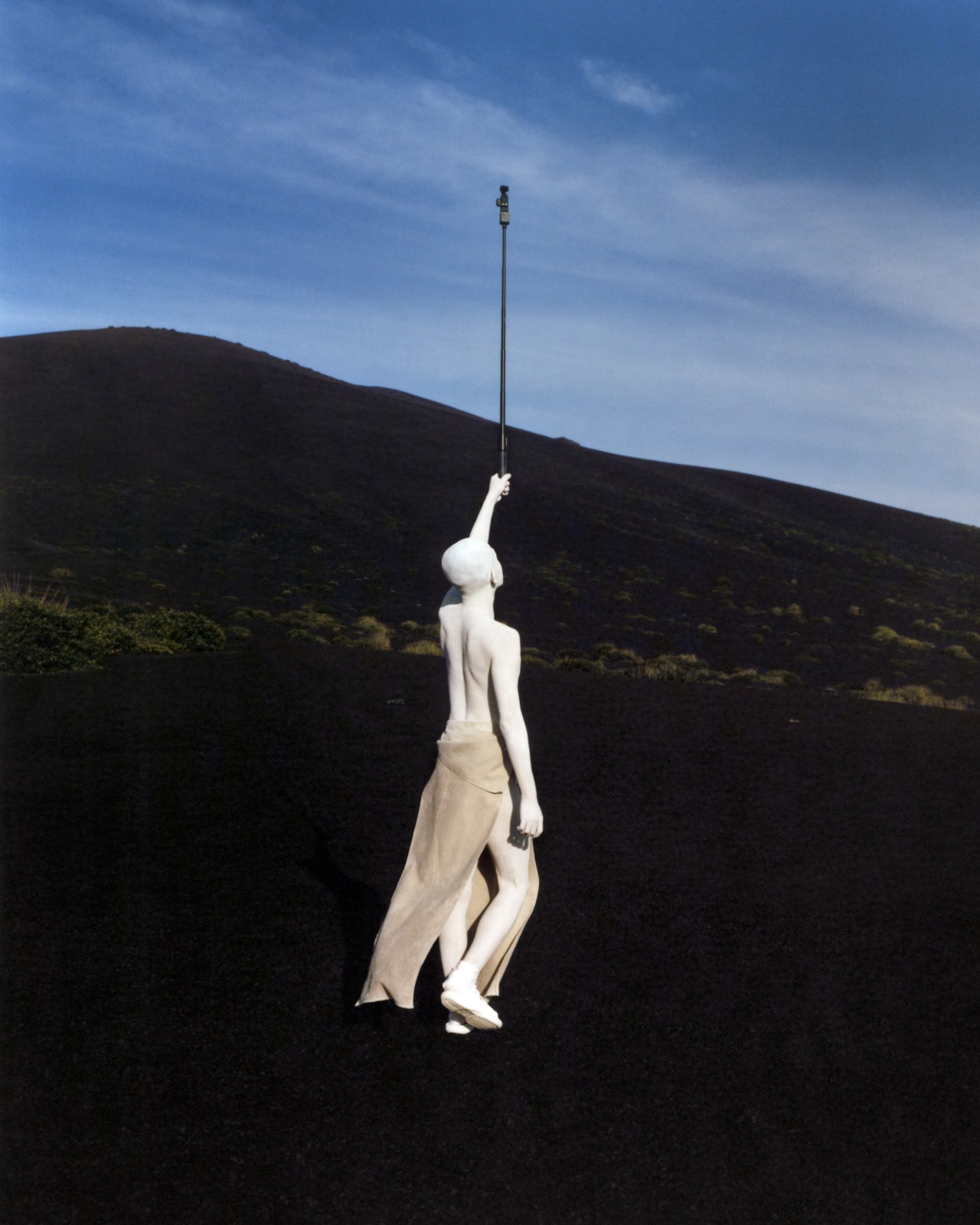

Photographs by Tom Johnson

words by jasmine hardy

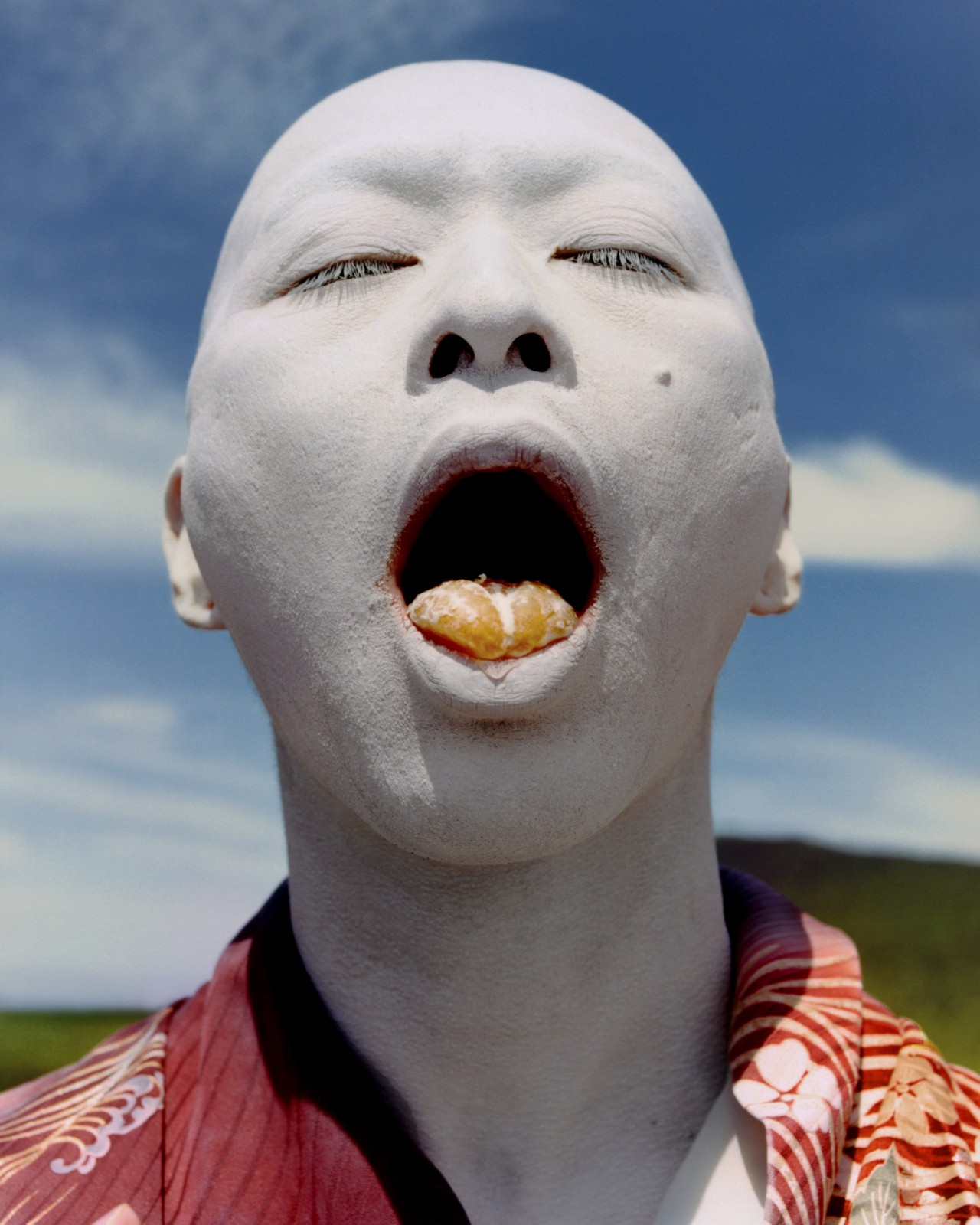

Butoh, a Japanese dance-theater art form characterized by slow dance moves, straddles both beauty and horror.

With shaved heads and painted white bodies, dancers contort their bodies as a form of visual language and unrestricted self expression. It’s a dance practice that can be traced back to the late 1950s, when it emerged as a reaction to a rapidly changing Japan in the post-war period, and in opposition to the growing influence of Western culture on Japanese art. With the cultural identity of the country in flux, butoh founders Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno felt it necessary to reclaim Japan’s sense of self and foster new national imaginations. Thus, the unique—and jarring—art form was born.

Absurdity, darkness, and struggle are all key markers of butoh. It dives into the depths of the individual body and psyche, unearthing buried feelings and emotions and translating them into movement. Informed by Japan’s scorched landscapes, caused by America’s atomic bomb attacks on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945, artists examine themes of death, decay, and regeneration to create necessary space for building a renewed identity—one in deep connection to the Earth. Butoh’s focus has always been on the physical expression of the Japanese body, and specifically, the Japanese common person, reflecting their intrinsic ties to nature. Over the years, this bodily kinship with the planet offered a path through which forgotten identities could return.

Today, butoh is still understood as a form of dialogue between dancers and their environment as the dance exists in relation to—and evolves alongside—the setting it is performed in. These photographs, which first appeared in Atmos Volume 10: Afterlife, document Japanese butoh dancers performing on the ever-changing landscapes of Japan’s Oshima island. Below, lead dancer, Norihito Ishii, sits down with photographer Tom Johnson to discuss body expressionism as the core foundation of butoh, and the importance of preserving this cultural practice for future generations.

Tom Johnson

Butoh is known for its unique physicality and expression. How would you describe the core techniques of butoh to someone unfamiliar with the dance?

Norihito Ishii

Whereas many world dances are based on technique, the foundation of butoh is in the imagery, the virtual environment of the body’s inner and outer worlds, and the textures and emotions within it. The emphasis is on how the body should exist and move within this environment. The core of butoh is not the beauty or technique of the body in the Western aesthetic sense, but the outward expression of feelings and awareness that emerge from the inner world of the body.

In my opinion, in general, dance technique is the framework on which expression is clothed as a “skin,” but in butoh, expression itself becomes the framework, and as it continues, the technique becomes the “skin” as a result.

Tom

Butoh often explores themes of darkness and transformation. How do you choose the themes for your performances, and what message or emotion are you aiming to convey?

Norihito

Butoh has a “style” and [in some instances] a vocal style that accompanies the choreography, but we do not choose this as the theme of our work nor do we try to convey it to the audience. Each butoh dancer has a different method and philosophy, and neither myself nor the Sankai Juku to which I belong, perform in order to convey a specific message to the audience.

In my opinion, we simply create certain phenomena and events on stage and present them to the audience. Each audience member comes from a different background and has a different experience, so it is up to each of them to decide what they feel. I don’t want to present any particular message to the audience, but rather for each person to take away with them how they feel about the phenomenon or event that happened at that moment—and then how they can reflect on it in their life afterwards.

Tom

Butoh is often said to have a deep connection with nature. How does the natural environment influence your work?

Norihito

The natural environment is universal. We are sensitive to the processes and energies of nature and incorporate them into our physical expression, such as the sensation of the wind on our skin; of being swept away by waves; of rain moistening the soil; or the slow rhythm of plant growth. For example, the body may move as if swept along by the wind or waves, or the dazzling movement of looking at the sun, or the process of a flower slowly blooming, which is felt in the body and translated into movement.

Nature is a symbol of a shifting existence, and the transformation and transience of nature and the cycle of the seasons are often incorporated into the “patterns” of butoh dance.

Tom

What makes Izu Oshima island a unique and compelling location for a butoh dance performance?

Norihito

I think it is a strong place that is both realistic and surreal. It has a strong energy as a place, it is spectacular in nature, and I found it an attractive and supportive place that helps us create a surreal setting.

Tom

How do you see butoh evolving in contemporary Japanese culture? Are there aspects of traditional butoh that you feel are being preserved or transformed?

Norihito

Butoh is a physical expression that is anything but conventional. I started with street dance, then went on to contemporary dance before studying butoh and joining Sankai Juku. Butoh has evolved considerably since the 1960s as each butoh dancer has established their own method and philosophy of expression. On the other hand, it is not certain to what extent the classical methods and philosophies have been passed on to the next generation. This is because, while butoh is known worldwide, the culture is in decline in Japan.

Tom

What future directions or innovations are you interested in exploring within butoh? Are there any new projects or ideas you’re excited about?

Norihito

Although it varies from country to country, we want to convey the strong imaginative power of butoh to people of all ages, from children to the elderly. Butoh is free, and you can choose what is right for you.

Butoh is in decline in Japan, but we are exploring ways to enjoy butoh as entertainment and how it can be presented to contemporary society as a conceptual art. Also, while butoh is spreading around the world, there are many butoh practitioners who have inherited only the superficial aspects of the art.

My base is the butoh of Sankai Juku, and I want to convey the essence of butoh throughout the world while both defending and breaking away from it. I hope to develop my own method and my own works.

Talent Norihito Ishii, Kana Nakamura, Toshitaka Matsumoto, Fumihiro Yoshino, Daiki Iwamoto, and Yusuke Kawabata production Jeremy Joyce (Hinoki Productions) and Alexandra Marshall (Mini Title) production manager Kenji Baraki and Cristal Ono casting Taka Arakawa photography assistant James Hobson production assistant Joshua Helius PHOTOGRAPHER AGENT Kate Clarence (Mini Title) OSHIMA ISLAND COORDINATOR Takahiro Sato

Correction,

December 4, 2024 7:33 am

ET

This story has been updated to clarify the affiliation of the Japanese Butoh dancers featured in the story. They are a collection of independent dancers, not a dance group.

The Dance of Darkness: Inside the World of Japanese Butoh