WORDS BY NEIL VORA, MD

Illustration by Landis Blair

The movie Outbreak changed my life. I watched it as a teenager and instantly grew enamored with the idea of chasing dangerous diseases in a hazmat suit.

Now, for over a decade, I’ve had the privilege of living that dream. In 2012, I joined the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). During my time with CDC, I traveled to west and central Africa to fight the two biggest Ebola outbreaks ever, led the investigation of a newly discovered smallpox-like virus in the country of Georgia, and vaccinated raccoons for rabies from an airplane in Ohio. And, during the worst acute public health crisis in a century, I oversaw COVID-19 contact tracing for New York City, perhaps the most challenging role of them all. These days, I split my time between treating patients with tuberculosis (TB) and working for Conservation International, an environmental nonprofit, where I advance public health in a new way: by protecting nature for people, such as by keeping tropical forests standing to prevent the emergence of novel infectious diseases.

This work feeds my soul, but dealing with existential threats such as pandemics and climate change on a daily basis can take its toll. To help manage my anxieties about the fate of the world, I often turn to scary stories about contagions and other doomsday scenarios. This may seem counterintuitive, but I find the horror genre to be a perfect sandbox to explore pressing societal problems without real-world repercussions. Horror allows me to navigate my fears to their extremes from the comforts of my living room.

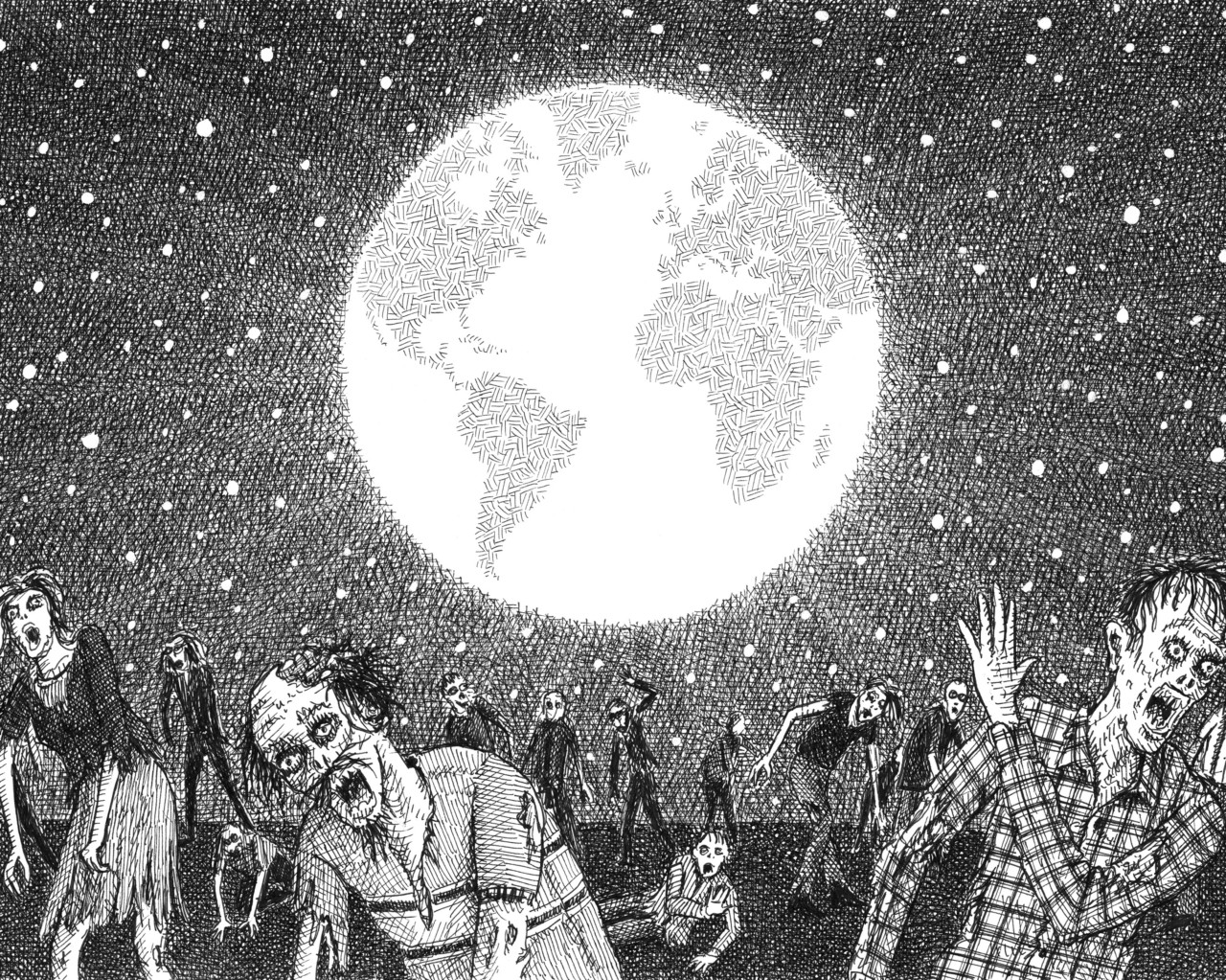

I’ve therefore delighted in the recent proliferation of post-apocalyptic zombie pop culture. Films like 28 Days Later and its sequel 28 Weeks Later (my two favorite horror films ever) explore the complex intersection of the “spillover” of viruses from animals to humans, crowding in cities, and international travel. More recently, the HBO show The Last of Us went two steps further to explore the growing threat of fungi in the face of climate change.

These nightmarish stories can be seen as morbid omens. They reflect our collective trauma from increasingly frequent outbreaks of frightening infectious diseases, from anthrax to Zika, HIV to mpox, Marburg to avian flu, and others. They mirror our concerns about the state of the planet, with record heat, dreadful natural disasters, and widespread species extinction. But while fictionalized catastrophes help me grapple with my worst fears, I’ve also come to realize that consuming them without a critical eye can lead to a paralyzing level of despair—a luxury we can’t afford at this pivotal moment in history.

Conjuring monsters to wrestle with the unknown is nothing new. In the 1700s, for example, vampire lore flooded Europe. There’s good reason to believe that this vampire hysteria was inspired by two infectious diseases—rabies and TB. Not surprisingly, people with these diseases back then had awful outcomes. Even to this day, rabies and TB kill approximately 70,000 and 1.3 million people per year, respectively. But the germ theory of disease that is now pervasive had yet to be popularized—so people instead resorted to supernatural explanations.

Consider rabies. The bite of an infected animal—particularly bats and canids such as wolves—triggers aggression, insomnia, hypersexuality, and avoidance of light, among other things. Sounds eerily similar to vampires, no?

TB, historically known as “consumption,” causes a chronic illness involving weight loss and coughing up blood. By the time its victim dies, other family members catch the lethal bacteria and start getting “consumed” themselves—as if loved ones were coming back from the grave each night for a blood meal.

Communities sometimes went on to exhume corpses to slay the vampire they thought laid below. What they saw only confirmed their deepest fears. After burial, a corpse can bloat with gas as it decomposes—as if a meal were recently devoured—pushing blood into the mouth and forcing the vocal cords to move in a way that creates gasping sounds. Skin and gums also retract, leading to the appearance of long, claw-like nails and fanged teeth.

As society’s fears have surged from localized threats to the globalized ones of the 21st century, these sorts of horror stories haven’t changed in kind, but in scale. Tales involving a single monster like Dracula have given way to frenzied onslaughts of thousands—if not millions—of monsters at a time. Just look at the growing popularity of zombie pandemic entertainment: World War Z, I Am Legend, The Walking Dead, and countless others.

This nihilist impulse is a bigger threat than any ghost, werewolf, or other terror—because hopelessness is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

As much as I enjoy these modern dystopian depictions, I admit, they’re misleading. While they help us diagnose the threats we face, they fall short on remedies even when they exist. They present the end of the world as inevitable. They feed a pernicious, centuries-long theory some hold about human behavior: that the “thin veneer” of order and governance keeping society afloat can shatter at any moment, giving way to innate, brutish human tendencies. This nihilist impulse is a bigger threat than any ghost, werewolf, or other terror—because hopelessness is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Here’s the thing: pessimism is not just intellectually lazy and unoriginal. It’s also false. Humanity is capable of incredible things. Our ingenuity is all around us.

Every time I’m in clinic treating patients for TB, I’m reminded that 80% of those with the disease used to die because effective antibiotics weren’t available. After the horrors of early 2020, scientists developed a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine saving tens of millions of lives. In 1970, nearly half of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty; now that rate has plummeted below 10%. Globally, people live longer, literacy has nearly tripled in the past century, and homicide rates are the lowest they’ve been in 40 years.

We have incredible solutions for climate change, too. The cost of solar power has fallen dramatically, and we’re transitioning away from fossil fuels; countries are signing on to increasingly ambitious climate and biodiversity commitments; and nature is one of the few political issues both sides can agree on.

Facts are the currency of my work as a physician and epidemiologist. But science alone can’t solve the existential threats facing the world today. It will also take a radical reimagination of our future—inspired by art and philosophy—to catalyze the societal transformation that is desperately needed.

Horror stories are a critical tool for that purpose and could be made even more powerful by holding dread and hope in greater balance. Humanity has thrived in the face of adversity since the beginning of our history. We are far from perfect, but we’re resilient. Time and time again, people have overcome the most cynical predictions. We can—and will—do the same for the real-world terrors stalking us right now.

How Zombies and Vampires Help Me Grapple with Disaster