It’s official: Tamagotchis are back.

Bandai, the company behind the famous handheld digital pet that first launched in 1997, saw global sales double between 2022 and 2023, according to the BBC. In September, Bandai opened the first Tamagotchi flagship store outside Japan in the United Kingdom.

Tamagotchis aren’t the only iconic ‘90s gadget to experience a revival. Vinyl record and CD sales are through the roof, telecom companies are recreating dumbphones, and lo-fi digital and disposable cameras are making a comeback along with Pokémon, Furbys, and Bratz—the latter thanks to Kylie Jenner’s new line last year. Last weekend also saw the release of A24 production company’s latest film, Y2K, which follows two high schoolers who crash a 1999 New Year’s Eve party that turns nightmarish when ‘90s gadgets come to life and attack humankind.

As many of us are finding joy and entertainment in the rebooted toys of our childhood, the climate crisis rages on. That’s no coincidence. In 2022, The Atlantic proclaimed nostalgia as the dominant emotion in the era of climate change, and just a couple of years earlier, The New York Times assured readers that nostalgia is a natural response to polycrisis.

“We are in need of comfort and ways to engage in self-care because we know that the cards are stacked up against us right now,” says Britt Wray, author of the climate-mental health newsletter Gen Dread and director of the CIRCLE initiative at Stanford Psychiatry, which stands for Community-minded Interventions for Resilience, Climate Leadership and Emotional Wellbeing. “Nostalgia, as an increasingly popular phenomenon amongst youth, makes sense once you start thinking about the chronic insecurity many people are feeling in this age of climate crisis, political turmoil and polarization, increasing inequality, an affordability crisis and so on. It’s a very human reaction to want to crawl under the covers and ignore it all.”

Enter nostalgiacore, a trend that’s taken the internet by storm by tapping into the emotional allure of the past, characterized by the revival of clothing styles, toys, and tech from the 1990s and early 2000s. But some experts say nostalgiacore is much more than just an aesthetic: It’s a cultural coping mechanism for climate anxiety and doomism. After all, nostalgia is comforting; it soothes by evoking memories of supposedly simpler, more stable times—an advantage that’s been leveraged by politicians, who have turned nostalgic language into a cornerstone of populist political rhetoric.

But can harking back to a time of mindless overconsumption offer meaningful ways of coping in an age defined by climate collapse? The answer is not so straightforward. As Professor Lawrence Quill, author of Nostalgia and Political Theory, cautions: “Thinking carefully about nostalgia shows us just how easily we can be tripped up by views or ideas about the past that aren’t really terribly accurate.”

Generation Z is the most climate anxious demographic. It’s also very nostalgic.

Eighty-five percent of Gen Z-ers say they are feeling worried about the impacts of the climate crisis, according to studies, and 15% say they would rather think about the past than the future. Gen Z, alongside Millenials, are also by far the biggest consumers of nostalgiacore, which is driven in large part by social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram; #nostalgia has more than 11 million posts on TikTok, many harking back to gadgets and games from the 1990s and 2000s, and #Y2kAesthetic and #Y2kFashion has accumulated over 500 million views. There are also dedicated accounts like 90s.talgic and nostalg1ac0re on Instagram with hundreds of thousands of followers.

It’s no surprise that people who feel overwhelmed by climate anxiety may turn to objects evoking stability, longevity, and familiarity. “Interacting with nostalgic items offers comforting, tactile sensory experiences where things appear to be not so complicated—and that provides associated feelings of safety and belonging,” Wray says. “Whether people are doing it consciously or unconsciously, [nostalgiacore] is partly a form of yearning for temporary relief from the affective experience of living in dangerous and complicated times where we are struggling with things like the climate crisis.”

“It’s a very human reaction to want to crawl under the covers and ignore it all.”

There is some historical evidence to back this up: The rise of collective nostalgia has time and again emerged during periods of social upheaval. Historians note that in the years after the French Revolution, for example, people reported feeling a collective longing for the “good old days” of the pre-revolutionary Ancien Régime. More recently, streaming companies during the COVID-19 pandemic reported a spike in classic sitcoms like Friends and The Office as people took refuge in familiar TV shows to help cope with global uncertainty.

Quill describes nostalgia during disorienting times as a “lifeline”—a way for people to anchor themselves during collective distress. But when nostalgia is on the rise, he says, it’s also important to ask: “What is it about the modern world that is so deeply unsatisfying or alarming that many young people look for solace in their past or the past of others—or displaced nostalgia? It is clearly a yearning for a better time, especially when faith in the future has been shaken.”

That faith in the future has been shaken is no understatement. In the past year alone, the world failed to meet critical climate targets, endured wildfires that devastated ecosystems across continents, and grappled with escalating geopolitical tensions that deepened global inequality.

Nostalgia is hardly a new emotional response to crisis, but the pace and scale of its commodification today are unprecedented. Nostalgia has very quickly become a marketable product—and brands have jumped on the bandwagon. From Y2K-inspired fast fashion to old toy reboots to retro-inspired gadgets, products that evoke times past have become a hot commodity.

Social media plays a pivotal role in amplifying and monetizing nostalgia by turning personal memories into marketable moments. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok thrive on curated nostalgia that’s also a fertile ground for targeted advertising. “Facebook introduced its timeline a little while ago along with Throwback Thursdays,” says Quill. “What is being consumed here, of course, are images, not products. But, what is being gathered during the nostalgic process is user-data, which is then shared with advertisers. So, commodities will be sold to users as a kind of nostalgic totem.”

It’s a serious issue that raises questions about the ethics of repackaging and selling our intimate emotions as commodities to maximize corporate profits. While nostalgiacore might seem like a harmless manifestation of our collective yearning, it paradoxically also risks perpetuating the very systems of environmental harm that have driven us to the brink in the first place.

“What is it about the modern world that is so deeply unsatisfying or alarming that many young people look for solace in their past or the past of others—or displaced nostalgia?”

So, where do we go from here? Justin Lawson, a lecturer in health ecology and planetary health at Deakin University, says it’s key that we reclaim the future by critically evaluating and amending—rather than pining for—the past. To Lawson, the first step is practicing environmental kinship. “My view is that to be aware of [nature], we need to immerse ourselves in it,” he says. “But granted, not everyone can and not everyone has the capability or capacity to immerse themselves, so we need to find ways that can bring nature to those who aren’t able to access nature, or have certain trepidations about it.”

The reality is that there’s a lot to learn about the power of movement-building by looking backward. “We [can use the rise of nostalgiacore as an opportunity] to return to those old values of reduce-reuse-recycle,” Lawson says. “Remember, the 3Rs [reduce, reuse, and recycle] was first promoted back in the 1970s, which gained traction in the 1980s and ’90s so it’s only fitting that we look to those eras for inspiration and develop the themes further to make a better impact and carry the flame.”

While Lawson urges an analytical reflection on history, Wray frames nostalgia used this way as a form of self-soothing, but stresses the importance of pairing it with tangible action. That’s the only way, she says, of effectively working with the anxiety and discomfort nostalgiacore is trying to alleviate.

“I don’t want to write it off as being only some kind of retreat from reality or escapism because there’s certainly a place and a time for this kind of comfort-seeking,” Wray says. “It’s just that we cannot hang out under the covers forever. We need to find ways of breeding up more hardcore existential resilience so that we can actually engage in transformative actions with others to build a better world rather than just hide away from the scary system in which we’re living.”

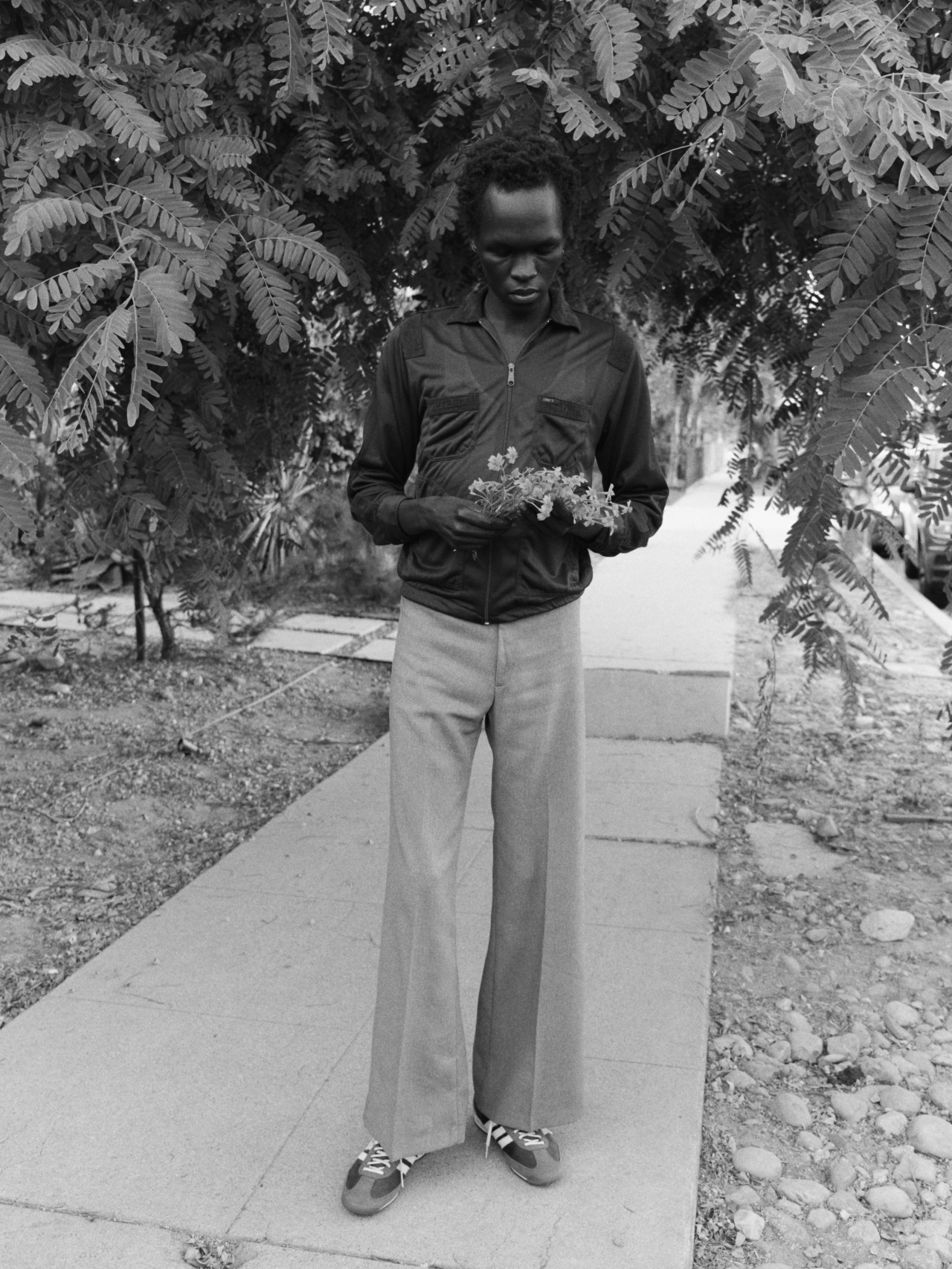

Styling assistant Gigi Bolant Makeup Karo Kangas Hair Dennis Gots Props Sala Johnson Casting Memoria Di Talent Jahsai, Delphine, Marwang, Christian, Courtney, Lila Special thanks Sam and O the bearded dragon Vintage clothing Squaresville, Sleeper, The Attic, James Veloria

How Climate Anxiety is Fueling ‘90s Nostalgia