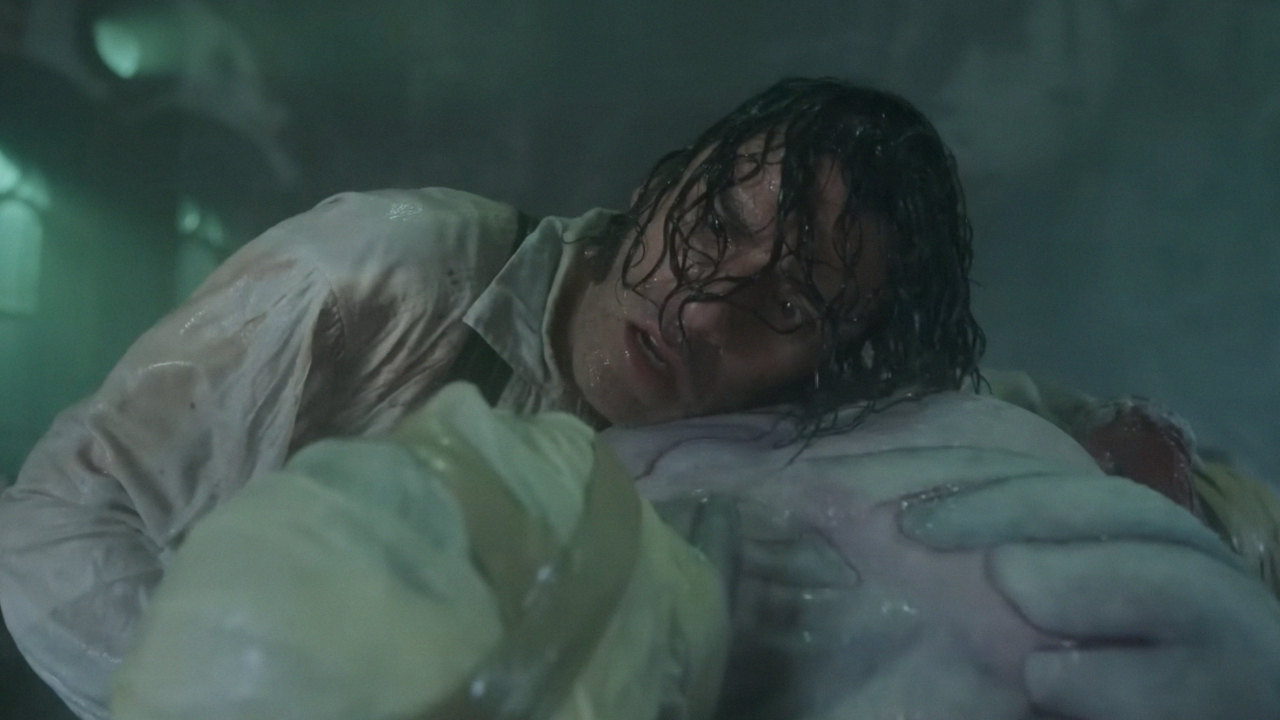

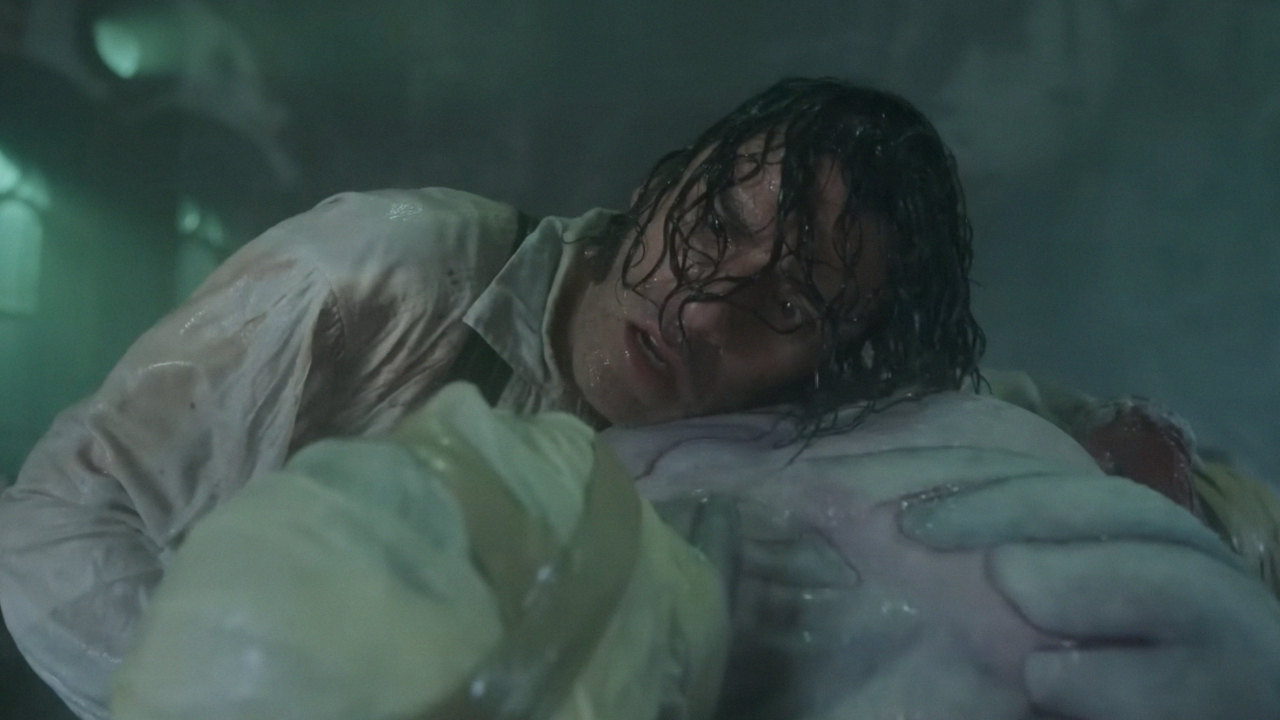

Photograph courtesy of Netflix

Words by Billie Walker

It was in 1816, during what became known as “the year without a summer”—when volcanic ash from Mount Tambora blotted out the sun and sent temperatures across Europe plummeting—that Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. A founding work of gothic fiction, Frankenstein unfolds amid the Alpine peaks and Arctic ice where Victor Frankenstein’s doomed experiment takes shape, landscapes that mirror the unseasonable chill Shelley herself endured.

More than two centuries later, in the Anthropocene Epoch of climate extremes and natural disasters, Guillermo del Toro revisits Frankenstein for a world facing its own monsters.

Del Toro’s film opens in the Arctic, where a team of sailors encounter Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac) and his Creature (Jacob Elordi) locked in anguish over the destruction the creation has unleashed. The story then cuts to Victor’s youth, unfolding chronologically from there. His father, Leopold (Charles Dance), is more a strict teacher than parent, intent on molding his son to follow in his medical footsteps. The warmth of his mother, Claire (Mia Goth), is short-lived: She dies in childbirth, leaving Victor to inherit his father’s cold ambition and grow into a man hellbent on scientific invention no matter the cost.

“No one can conquer death,” Victor says, as the idea for his experiment takes hold. “I will. I will conquer it.” In a fevered dream, he is promised “command over the forces of life and death.” The declaration captures Victor’s hubris and the film’s wider warning around humanity’s refusal to accept natural limits, the same impulse that has driven us to remake the climate in our own image.

In his diligent adaptation, del Toro insists we witness every grisly stage of Victor’s attempt to engineer a living being from the remnants of the dead, instead of skipping straight to the Creature’s electrified awakening as many other films have. We see Victor scour the battlefields of the Crimean War, selecting limbs from the fallen as if picking flowers for a grotesque bouquet, in his pursuit of perfection. The logic is simple: Amid the wreckage of war, he can find the youngest, healthiest bodies to assemble his Creature. And yet there are not one nor two, but three acts of resurrection, each ending in failure. Over and over, Victor’s obsession reduces creation to a parlour trick, and strips life of dignity and nature of reverence.

“In the Anthropocene Epoch of climate extremes and natural disasters, Guillermo del Toro revisits Frankenstein for a world facing its own monsters.”

What begins as an egotistical-if-well-intentioned scientific experiment to conquer death soon curdles into horror. As del Toro told Sight & Sound, “the dirt that follows the altruistic is always trailing blood.” Victor’s pursuit of creation leaves him surrounded by corpses, which he disposes of through a chute that plunges from his castle to the lake below in a chilling image of industrial waste and moral decay. The scene mirrors the wastefulness of modern life, where mass consumption and the drive for optimization through products, apps, and endless upgrades disguise exploitation as progress. Through Victor’s obsessive creation, fueled by his desire to, in his own words, “pursue nature to her hiding places to stop death,” Frankenstein becomes a parable for how unrestrained innovation corrodes human and ecological well-being.

Some viewers have read the Creature as a metaphor for artificial intelligence, an amalgamation of parts assembled into artificial consciousness. Del Toro has repeatedly denied this interpretation, but the comparison is nonetheless relevant. Victor channels his intellect and resources into a project that serves ambition, not the betterment of the world, like so many of today’s tech giants.

His wealthy patron, Heinrich Harlander (Christoph Waltz), only deepens the moral rot. Harlander bankrolls the experiment with profits from arms deals. As the war wanes, so does his investment, an irony that reveals how even the pursuit of eternal life depends on the machinery of death. Harlander’s motives are no less self-serving. He hopes Victor’s discovery will save him from mortality itself. Together, they embody a cycle familiar far beyond the screen. It is the same nexus of wealth, war, and technological obsession that drives real-world crises; and their vision of progress depends on a level of extraction and control that leaves little room for life to flourish.

“In del Toro’s vision, the true horror lies with those men, whose ambition and excess have created such stark inequality and turned the natural world against itself.”

There are plenty of modern-day Heinrich Harlanders, from billionaires privatizing scientific research to tech entrepreneurs like Bryan Johnson pouring fortunes into biohacking and anti-aging research, chasing immortality while the planet burns. With today’s technological advances and the rise of a billionaire class, Harlander is a disturbingly plausible figure intent on funding his own survival while the world collapses around him.

In the end, Victor’s meticulous planning and ambition amount to nothing. The moment of creation is thrilling, but his triumph dissolves instantly into despair. His achievement is “void of meaning,” he realizes. “I believe there is life in it,” he said, “but not the spark of intelligence.” Lady Harlander (Mia Goth) pushes back: “It is intelligent. Just not as you know it.” Victor’s failure echoes the modern faith in innovation as progress, even when it accelerates the very crises it claims to solve. Stripped of responsibility for what he’s made, Victor becomes the perfect emblem of a man addicted to creation for its own sake.

The Creature, by contrast, moves through the world with childlike wonder. One of his first gestures is to play with a leaf before offering one to Lady Harlander as a gift. Later, abandoned by Victor, he wanders through the forest, awed by its beauty, feeding berries to a deer just before hunters shoot the deer down. “What is it? Shoot at it!” they cry when they spot the Creature, who only longs, he says, for “the world and I [to be] at peace.” In del Toro’s retelling, it’s a brutal inversion: the so-called monster cherishes life, while men remain its most destructive predators.

Not everyone in Frankenstein shares Victor’s disregard for nature, nor do they recoil in horror at the Creature he brings to life. Some approach him with empathy, and through them del Toro restores a glimmer of humanity to the story. But the director is unsparing in his portrayal of Victor and the men he surrounds himself with. As Jacob Elordi recalled del Toro saying at the Venice Film Festival press conference, the real monsters of the world are “the men in suits.” It’s a line that crystallizes the film’s contemporary relevance. In del Toro’s vision, the true horror lies with those men, whose ambition and excess have created such stark inequality and turned the natural world against itself.

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein will premiere in limited release in the U.S. and U.K. on October 17, ahead of its global debut on Netflix on November 7.

‘Frankenstein’ Puts the Human Cost of Mastery Over Nature on Full Display