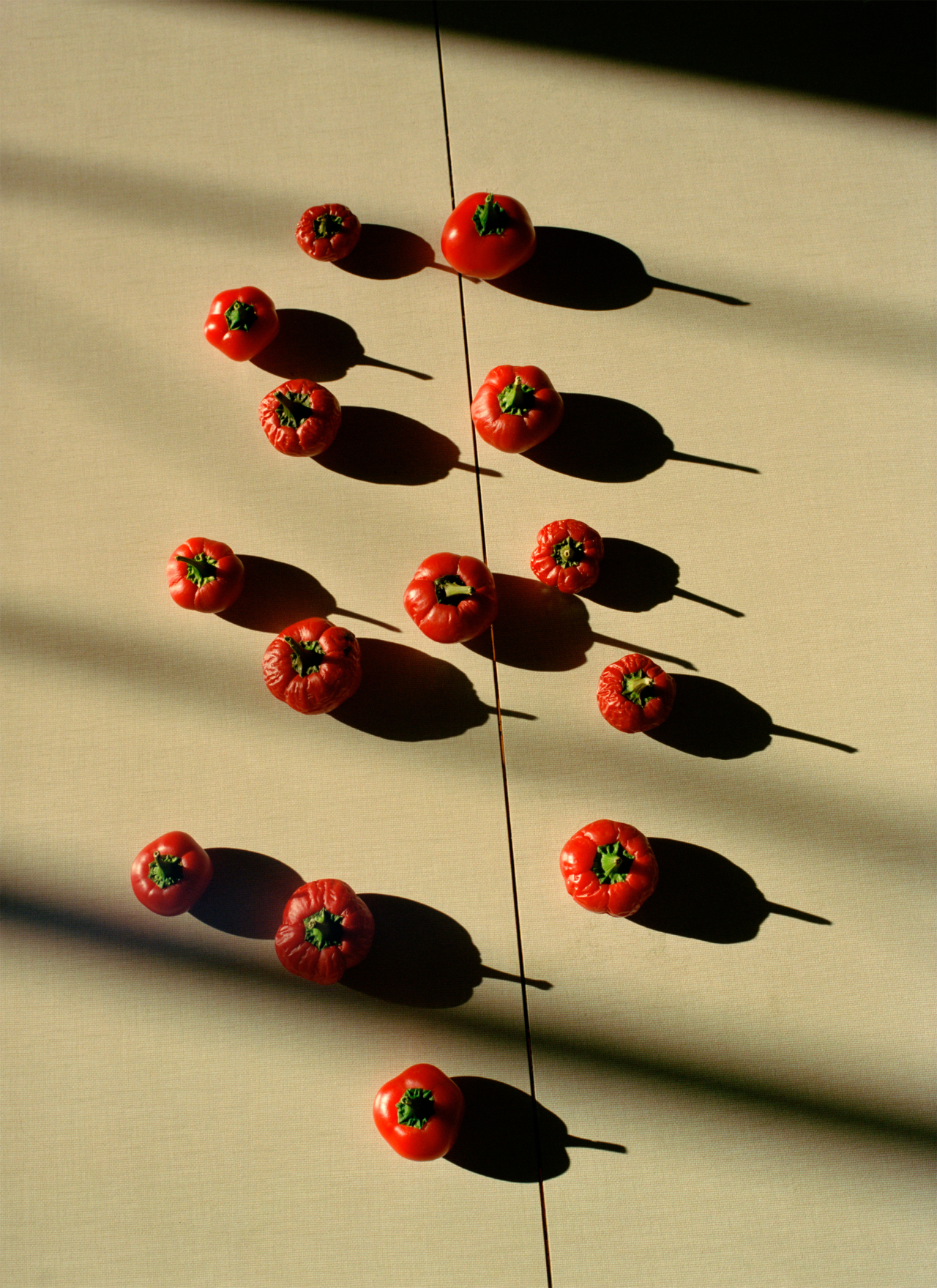

Photograph by Molly Matalon

WORDS BY JASON P. DINH

René Redzepi opens his new Apple TV+ docuseries, Omnivore, with the maxim, “You are what you eat.” The saying typically refers to health and fitness, but Redzepi, the show’s co-creator, executive producer, and narrator, takes it to mean so much more.

Redzepi, the chef-owner of Noma, a Copenhagen-based Michelin three-star restaurant and five-time champion of the World’s Best 50 Restaurants list, has spent the past two decades learning about food—not just how it fuels us, but how it connects cultures, buttresses economies, and powers politics. Food, then, is not only the clay from which our bodies are molded. It’s also a mirror in which our species’ greatest strengths and worst vices emerge.

Each episode of Omnivore shepherds viewers through the human story of a different ingredient: chili, tuna, salt, banana, pig, rice, coffee, and corn. Along the way, we experience our species at its best. We see how advancements in genetics and chemistry allowed us to nourish a booming global population, how engineering innovations emerged from a growing demand for tuna, and how a simple ingredient like a chili pepper connects people as distant as Bangkok and Louisiana’s Bayou—feats of ingenuity and cross-cultural connection.

We also see people at their worst. We meet workers at the base of the global supply chain who are being left behind by poor wages and dangerous working conditions. We witness how climate change and biodiversity loss threaten farmers’ harvests and livelihoods. We’re confronted with the cruel realities of industrial animal farming. We even learn that ingredients like coffee and bananas were at the root of some of the past century’s worst humanitarian disasters, like the Rwandan Genocide and Latin American political uprisings.

If we are what we eat, then Omnivore paints a complex portrait. Are we crafty and compassionate, or are we cruel, capable of inflicting ecological and social harm for a quick buck and a cheap eat? Maybe, we’re a little bit of both.

On a video call from Noma, Redzepi and writer, co-creator, and executive producer Matt Goulding joined Atmos to reflect on the show’s lessons ahead of its release.

Jason Dinh

René, I’m curious what inspired you to work on this docuseries. Was it related to your recent decision to close Noma?

René Redzepi

Actually, it wasn’t. The beginning of Omnivore dates more than 10 years back. It was a time when Noma was just getting to be known all throughout the world, and I was being offered TV shows. Of course, I was too busy at the time, but it did make me think, if I was ever to do TV, what would that be?

Very quickly I realized that the main inspirations I have for TV are the great nature documentaries. I loved them as a child. David Attenborough—I was a huge fan. The idea was simple: Can we make a show about food with the same dedication, care, inspiration, and scope that those nature shows have for a tiny beetle or a worm that sits under a leaf in an Amazonian forest? What would that make people feel? Could we instill a sense of awe and wonder about the stuff that we eat every day?

“What we eat dictates how healthy we are as a people. How we grow it dictates how healthy our planet is.”

Jason

You named the series Omnivore, and only two of the eight episodes highlight an animal product. That seems particularly relevant in today’s eating environment. We eat 55% more meat per capita than we did in 1970, and meat causes some of the worst environmental impacts of food. Meat production causes 11% to 17% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and beef in particular is the leading cause of deforestation worldwide. Was it a conscious effort on your part to highlight mostly plant-based ingredients throughout the series?

René

Yes. Throughout history, humans have eaten many more plants than they’ve eaten meat, so this show will always be much more plant-heavy. If we ever get to do a season two, three, or four, there will be very few animal products. You run out of animals very quickly because there are only four or five of them that we genuinely eat. The vast majority of our diet and society is built through the plant kingdom.

We’ve had reservations about beef, and we’ve wondered whether that could be a part of an episode. If we were going to do something like that in future seasons, we’d probably do what we did in season one, which is to show some of the best practices that are out there and let them be an inspiration. There are so many incredible methods for growing food today. Some of them are very traditional and ancient, and in the show, we are trying to highlight that as a path forward.

Jason

I was actually curious about why beef wasn’t present in the show. In the United States, the cultural conversation about meat eating really centers around beef. The conversation around climate does, too. I’d be very excited to see a future episode about it.

You mentioned ancient traditions, and your show highlights a dichotomy of time that I found striking. We have food traditions that have been around for thousands of years, and those traditions changed dramatically within mere decades. We’ve turned the food supply chain into something entirely new, and that comes with numerous issues that you documented around human rights, environmental damage, and so on. On one hand, I think that the pace of change is quite scary, but on the other hand, it offers a little bit of hope—that we can build something better quickly, too. Do you think that within our lifetime, we can make something healthier, more sustainable, and more ethical than what we have now?

René

Within our lifetime, absolutely. I am more hopeful about things than I am the opposite. And I’m not unrealistic. We need change, and I think it can happen.

Matt Goulding

Some pieces of the series give us hope. If you take a look at, for example, the tuna episode, you have a fish that went from, in a span of a hundred years, being a trash fish that was largely discarded or sold for cat food to becoming one of the most valued niche products in the modern world. As our appetites changed, we nearly ate this fish out of existence. We pushed the populations of the bluefin right to the brink of collapse. And right as we got to the brink, the stakeholders in the bluefin economy—the nations that fish it and move it around the world—got together and made some changes on quotas, on the way it can be captured. With those few small adjustments, suddenly the population has turned around. What we find is that in the food world, with a few twists of the wrist, a vicious cycle can turn into a virtuous one.

Above all, we want to bring not so much a list of things that people should and should not eat. That’s not really the goal of Omnivore. What we want to bring is context and scope so that people can understand where the food comes from. So people can understand that every time they eat, they’re making a choice—a choice for a certain kind of world that they want to live in. That may seem like a lot to take on in the daily rigors of our lives, but even if we can instill a little bit more awareness in the lives of viewers, then I think we’ve done our job.

“What we find is that in the food world, with a few twists of the wrist, a vicious cycle can turn into a virtuous one.”

Jason

The biggest takeaway from the series is that food is a reflection of who we are. We see a lot of the good—our ingenuity and our ability to make profound cross-cultural connections. But we also see the bad—how we’re willing to sacrifice the environment, laborers, and cultural traditions for convenience and profit. Taken together, what do you think the food stories that you documented say about who we are?

Matt

That we are incredibly complex beings with many different layers to who we are and how we interact with the world. If you take a look at the corn episode, for example, we feature two different versions of corn. We have the monocropped version from Iowa, and we have the milpa from southern Mexico. Both families behind those individual corn farms have the best intentions. They want to grow food for their communities, they want to feed their family, they want to live a decent life, and they want to continue with the work that their families before them did. But they’re both representative of different systems.

Obviously, the giant Iowa corn system has some real flaws, but that’s not to say that the answer is to turn everything into a milpa. Maybe what can happen is the Iowa corn farmers can listen a little bit more to the traditions and to the ancient wisdom that has been gathered over generations, and maybe the milpas of the world can utilize some of the best-in-kind innovation and technology. They can find that balance.

René

Yes, the idea of keeping a milpa a milpa, keeping its diversity and its hand harvesting and its hand seeding, but pouring money and technology into it to make it as efficient as possible—it’s inspiring. I think it can happen.

Matt

And when you look at polycultures, it is not just that they’re a cool, beautiful, romantic reflection of the past. They actually produce more food per square acre than a monocultural farm does. That’s an extraordinary discovery. It’s not just a romantic ideal. It’s a reality that could be pragmatic. That was really a metaphor for us. Do we want to be the monoculture, the species that stands apart from the rest of the natural world, or do we want to be part of the milpa, this great polycultural world, where everything is interconnected and in fact, we’re stronger when we’re interconnected?

Jason

One of the themes that resonated with me the most through this show was how in modern agriculture, humans have tried to dominate nature, but that nature always bites back. You show this by documenting how the fungus Fusarium is obliterating banana monocultures worldwide and how climate change is ruining rice harvests by altering monsoon seasons. From a farmer’s perspective, it’s pretty clear that nature is biting back. I’m wondering, from a chef’s perspective, have you experienced climate change affecting your work?

René

Definitely. In the early days of Noma, if we weren’t called Noma, we’d probably call ourselves the Weather Restaurant because we eat the weather. As a cook, every day we receive ingredients that are harvested and in season. But seasons are changing. Last year, we didn’t have rain for the first two and a half months of spring and summer in Denmark. It was crazy for our own garden at Noma. We had much less harvest. This year, we’ve had so much rain that it’s been a disaster for the flowering season, so we’ll have less fruit. I know a lot of the winemakers around Europe—they’ve had disastrous seasons in the past couple of years, which means that for us as a restaurant, we’ll have more expensive wines. I mean, we live it every day. We see it.

“The salt flats, the rolling coffee hills of Rwanda, the banana plantations of Central and South America—food is the absolute texture of the world that we’re looking at.”

Jason

I’ve noticed that a lot of the world’s top chefs seem to be returning to nature, either to conserve it or to draw inspiration from it. There’s Eleven Madison Park which went vegan. And recently, I spoke with Virgilio Martinez at Central, last year’s World’s Best Restaurant, who uses only local Peruvian ingredients and anchors their whole menu around the ecology and microenvironments of their country. Is this reconnection with nature a broader movement that you see unfolding across the culinary arts? And is this something that you plan to carry with you as Noma enters its next phase?

René

Absolutely. Of course. It’s everything I live for. It’s what I believe in, and I wish Noma to be spending the vast majority of our time actually tackling and dabbling in bigger projects and bigger collaborations beyond just cooking for 40 or 50 people a night. That’s what the future holds for us.

I do see that as a larger movement that’s happening more and more within the food space because as cooks, you sit right in between the consumer and people who are growing food. Once you start spending time in a forest and harvesting wild snails and wild plants, you see what’s happening there, and you can’t look away. You want to help because you care for it, and you’re living with it every day. It is a new thing that’s happening. You wouldn’t have seen that 20 years ago in the top restaurants of the world—most definitely not.

Matt

If I could say something because René won’t say this himself: A lot of that movement starts right here at Noma. Time and Place was the title of their first cookbook, and it’s always been at the core of their ethos. Food is nothing if not time and place, and we have no sense of that in the modern food world. Watching what Noma has done over the years has always been one of the reasons I’ve admired René so much. When he called to say let’s make a television show, it made perfect sense, because he, in everything that he does, reflects this idea that food is the natural world.

It’s cool to see that movement happening at high-level restaurants because it’s not just about the people eating there every night. It’s like throwing a pebble in a pond—those ripples are really profound. They affect farmers, producers, and other people tied to these restaurants. Even if you look at the series, what we tried to do is to show how much the natural world is actually physically and aesthetically shaped by the food that we eat. The salt flats, the rolling coffee hills of Rwanda, the banana plantations of Central and South America—food is the absolute texture of the world that we’re looking at.

Jason

What is the most important lesson that you hope people walk away from your show with?

René

Food is the most important thing we have on Earth. What we eat dictates how healthy we are as a people. How we grow it dictates how healthy our planet is. And we need to value it much more than we do now.

Matt

That’s really it. That’s absolutely at the heart of Omnivore. I think it’s also a reminder that every time we engage with food, we’re not passive. We’re actively involved in this whether we know it or not. That should feel empowering. It should be inspiring. It’s not a lesson in all the things that we’re doing wrong, but an opportunity to do things right.

Omnivore debuts on Apple TV+ on Friday, July 19.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For Omnivore’s René Redzepi, Food Reflects Who We Are